Advertisement

Roger Nash Baldwin (1884–1981), one of the principal founders of the American Civil Liberties Union, was born in Wellesley, Massachusetts, to a wealthy Unitarian family with deep New England roots. “[S]ocial work began in my mind in the Unitarian Church,” he wrote, “when . . . I started to do things that I thought would help other people.” As a youth, Baldwin admired Henry David Thoreau and other “gentleman radicals” who combined rugged spirit with cultural refinement, and he absorbed his family’s patrician values of service and education. His aunt Ruth Standish Baldwin, co-founder of the National Urban League, introduced him to progressives like Felix Adler, founder of the Ethical Culture movement.

Like many sons of upper-crust New England, Baldwin attended Harvard. After completing a master’s degree in anthropology, he was hired as Washington University’s first instructor in sociology. In St. Louis, he delved into social work, directing a settlement house and working in the juvenile courts, and befriended more social reformers, including the anarchist Emma Goldman. As the United States entered World War I, Baldwin helped establish the National Civil Liberties Bureau (NCLB) within the American Union Against Militarism to defend conscientious objectors. Baldwin himself served jail time for refusing to enlist. In 1920, the NCLB became the American Civil Liberties Union, with a mission to defend all freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution and U.S. law.

Although often linked to the political left, Baldwin and the ACLU championed causes across the political spectrum, from workers’ rights to unionize to Henry Ford’s right to critique unions. By representing the least sympathetic defendants, like the Ku Klux Klan, Baldwin believed that the ACLU would help America embody the democratic principles of its founding documents. In his four decades as director, the ACLU was shaped by Baldwin’s powerful personality and vision, as well as his contradictions. A devoted enemy of poverty and oppression, Baldwin nevertheless preferred the company of those from his own social milieu. A one-time member of the Industrial Workers of the World and friend to many socialists and communists, he helped eject ACLU co-founder and communist Elizabeth Gurley Flynn from the ACLU in 1940, ironically setting the precedent for “loyalty” measures the ACLU later fought.

Under Baldwin’s leadership, the ACLU took part in landmark legal cases, including the 1925 trial of Tennessee teacher John Scopes (convicted of teaching evolution), and challenges to the WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans. Though these cases were lost, they succeeded in shifting national debates and public opinion. The ACLU prevailed in other Supreme Court decisions, including Brown v. Board of Education (supporting the NAACP), Miranda v. Arizona (guaranteeing suspects be informed of their rights before police questioning), and Obergefell v. Hodges (affirming the freedom to marry in every state).

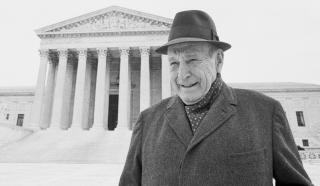

Baldwin devoted his later years to universal rights and founded the International League for Human Rights. He died at age 97 and was celebrated in a memorial service at the Community Church of New York (Unitarian Universalist). His organization remains a lightning rod in American life, viewed by some as a champion of dangerous radicalism and by others as the legal conscience of our nation. Upon receiving the Medal of Freedom in 1981, Baldwin described liberty as an ongoing practice of healthy democracy: “Never yield . . . your courage to fight, to resist . . . to be free.” Echoes of that determination were heard in November 2016, when a newly elected U.S. president appeared to regard civil rights as flexible guidelines. The ACLU responded simply: “See you in court.”