Advertisement

With the popcorn, toast, and jelly beans eaten, Charlie Brown and his friends pile into the back of a station wagon headed for Thanksgiving with Charlie Brown’s grandmother. As the car gains speed, the Peanuts gang breaks into cacophonous song: “Over the river and through the wood, to Grandmother’s house we go …”

By the time the Peanuts characters first sang “Over the River and Through the Wood,” the song had conjured Thanksgiving images of crisp autumn days and pumpkin pie for generations. Originally titled “The New-England Boy’s Song about Thanksgiving Day,” the piece appeared in the 1844 book Flowers for Children, Volume 2. Its author was writer, editor, and activist Lydia Maria Child, whose cozy holiday verses give no hint of the radical social justice ideals at the core of her work, most notably An Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans, published in 1833.

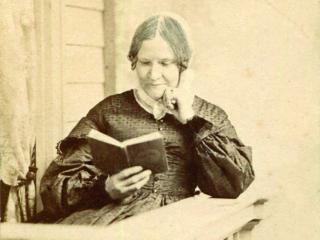

Lydia Maria Child (1802–1880) reading in 1870. (Courtesy Wayland Historical Society)

The fifth child of a Calvinist baker and his wife, Lydia Francis was born in 1802 in Medford, Massachusetts. Growing up, Lydia felt neither wanted nor loved, writes Lori Kenschaft in Lydia Maria Child: The Quest for Racial Justice. Her parents did not encourage education, but her older brother Convers gave her books, continuing to mentor her through letters after leaving home for Harvard when Lydia was nine.

Three years later, in 1814, Lydia’s mother died. Lydia moved to Maine to help her newlywed sister and brother-in-law. There, she met Penobscot and Abenaki Indians. The strength and skills of the Native American women left a lasting impression on Lydia, who understood that “these things that my culture says are impossible [for women to do] … that’s just not true, because I’ve seen it,” Kenschaft says.

Lydia lived and taught in Maine until 1822, when she moved to Watertown, Massachusetts, to live with Convers, who was by then a Unitarian minister. In Watertown, she took the name Maria and began writing. Her first book, Hobomok: A Tale of Early Times, appeared in 1824. Hobomok tells the story of a white woman and a Native American man who have a child together. Not often explored at the time, the theme hinted at Child’s inclusive views of racial equality. Two years later, Child founded The Juvenile Miscellany, the first American children’s magazine.

Lydia met David Lee Child, a Boston lawyer, journalist, and abolitionist, in 1824. Before their meeting, she was wary of marrying, and she accepted David’s proposal only after deliberating for four hours, according to Kenschaft, who describes David as “problematic.” However well matched the Childs were, David was clearly a financial liability. From libel suits to sugar beets, his activities leached a steady stream of money from the couple’s coffers.

Consequently, Lydia’s earnings disappeared quickly. David’s financial carelessness drove her to become financially independent from him in 1843, an “incredible decision” for a nineteenth-century woman, according to Jane Sciacca, past president of the Wayland Historical Society. The situation also spurred Child’s prolific writing, including her best-selling The Frugal Housewife (later renamed The American Frugal Housewife), a guide to keeping house on the cheap.

Child’s career was on track, with The Juvenile Miscellany thriving, when abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison’s writing took hold of her conscience. She became not simply an early abolitionist, but a radical Garrisonian convinced that “Without a changed public sentiment toward blacks, freedom from slavery would … be largely meaningless,” according to Milton Meltzer and Patricia G. Holland, editors of Lydia Maria Child: Selected Letters, 1817–1880.

Child joined the Boston abolition movement and wrote An Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans. The book persuaded many, including future senator Charles Sumner, that slavery was wrong. It enraged many others, who cancelled their subscriptions to The Juvenile Miscellany. Child’s book sales (and income) fell, never recovering to their pre-Appeal levels.

Nonetheless, Child remained dedicated to abolitionism. She moved to New York in 1840 to edit the National Anti-Slavery Standard. Two years in, the movement’s internal politics triggered her resignation. Child retreated from organized abolitionism, but continued to write for the cause.

Though she was initially resistant to women’s rights, Child’s views about them shifted. She wrote The History of the Condition of Women, in Various Ages and Nations in 1835, and eventually co-founded the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association in 1870.

Child’s belief in “equality and fairness toward everyone” underpinned her work, says Sciacca. Though Child never officially joined a church, she “was in Unitarian circles,” according to Kenschaft. As a Unitarian minister, Convers brought spiritually inclined thinkers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson into Child’s sphere, and Margaret Fuller became a close friend.

Child later explored religion with her 1855 book, The Progress of Religious Ideas, a three-volume study of the world’s religions. Years later, Child wrote Aspirations of the World: A Chain of Opals to “show that … The fundamental rules of Morality are the same with good men of all ages and countries …” Toward the end of her life, she attended the Free Religious Association in Boston, whose founders were Unitarians opposed to a strictly Christian reading of their faith.

Today, Child has a small, dedicated following—there’s even a nascent Lydia Maria Child Society in the works. Her evident humanity leaves as deep an impression as her writing and activism. Financial concerns and bouts of depression were intertwined with her work. Letters in beautiful handwriting reveal a deep concern for friends and a strong bond with David that survived their marriage’s complexities. Human as she was, Lydia Maria Child made history, shaped history, and entertained with her writing, far beyond her Thanksgiving classic.