Advertisement

The Unitarian Universalist Association was not quite four years old when the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. sent an urgent telegram to its Boston headquarters on March 7, 1965, asking religious leaders and concerned citizens to join him in Selma, Alabama, where African Americans marching for their right to vote had been brutally attacked by lawmen. Two of the Unitarian Universalists who responded to King’s appeal paid with their lives. In a way that few deaths do, the murders of the Rev. James J. Reeb and Viola Gregg Liuzzo helped change the course of history. But [in 2001,] 36 years after the protests that culminated in the march to Montgomery, new aspects of the story are coming to light. How unfinished our relationship to the past is.

James Reeb had been in Alabama less than a day when white assailants attacked him and two other white Unitarian Universalist ministers on a Selma sidewalk, fatally injuring him with a blow to the head. Reeb’s death on March 11, 1965, inspired a wave of nationwide protests, memorial services, and calls for federal action, transforming Reeb into a martyr and creating the political groundswell President Lyndon Johnson needed to introduce new voting rights legislation. Four days after Reeb’s death, Johnson invoked his memory—“that good man”—as he introduced the Voting Rights Act to a joint session of Congress. Johnson had invited King to attend the historic speech, but King turned him down in order to deliver James Reeb’s eulogy in Selma the same day. Somehow King’s eulogy has never appeared in print—until now. ( Listen to the recording of King’s eulogy UU World transcribed; read about the discovery of the recording.

About 500 Unitarian Universalists, including nearly one-fifth of all Unitarian Universalist ministers, plus laypeople like Viola Liuzzo, went to Selma and Montgomery to participate in the civil rights campaign. Only one Unitarian Universalist, the Rev. Richard D. Leonard, joined the 300-person march all the way from Selma to the state capitol in Montgomery. The trek concluded Leonard’s 18 days in Alabama. The UUA’s Skinner House Books is preparing to publish the compelling journal he kept, along with other Unitarian Universalist reminiscences of Selma. Part of Leonard’s unpublished journalappears here for the first time. (ReadCall to Selma: Eighteen Days of Witness , ed. by Richard D. Leonard; Skinner House Books, 2002.) Another Unitarian Universalist, photojournalist Ivan Massar, also went to Selma. His credentials with the (ironically named) Black Star photo agency alarmed town officials, who refused to issue a press pass—so he hid his cameras in his coat. Now retired and living in Concord, Massachusetts, he shared his photographs with us, some of which have never appeared in print before. (SeeUU World, May/June 2001, pages 25-27.)

This spring [2001], the Unitarian Universalist Association will dedicate a new monument to the hundreds of Unitarian Universalists who took a stand for civil rights in Selma. The monument, which will be installed in Eliot Chapel at the UUA headquarters in Boston, will commemorate James Reeb and Viola Liuzzo. It will also commemorate the first martyr of the Selma campaign, 26-year-old African American civil rights activist Jimmie Lee Jackson, whose death launched the march to Montgomery. Many African Americans noted bitterly at the time that Jackson’s death did not generate a sympathy call from the president of the United States, but that Reeb’s death did. The president himself announced the arrest of four Ku Klux Klansmen charged with shooting Viola Liuzzo as she drove back toward Montgomery to pick up more weary marchers, but no one was arrested for the gunshot that killed Jackson. Although Unitarian Universalists who arrived in Selma for Reeb’s memorial service learned about Jackson’s memorial service there only two weeks before, Unitarian Universalists haven’t always remembered him. This magazine revisited Selma in 1996, but the story made no mention of Jackson. The UUA’s monument will place Jackson, Reeb, and Liuzzo side by side.

Filmmaker David Taylor, producer of Crossing the Bridge, a documentary about Selma that aired in February on the History Channel, drew on recently declassified recordings of President Johnson’s telephone conversations during the months of the Selma campaign. Taylor traced the idea for the march to Montgomery to James Orange, a staff member of King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Orange responded to Jackson’s death by proposing that they carry Jackson’s casket all the way to Governor George Wallace in Montgomery. Although they abandoned the idea, the SCLC announced at Jackson’s memorial service on February 26, 1965, that a march to Montgomery would begin on Sunday, March 7. Taylor found that Jackson’s death “had a profound impact on the reporting on Selma,” convincing the media of the nonviolence of the protestors and the brutality of their opponents. President Johnson may never have mentioned Jimmy Lee Jackson, but the march that began in his honor carried the most important civil rights legislation in 100 years into law.

Unitarian Universalists rallied to the civil rights cause in Alabama, and Selma energized the new UUA. Before returning home from the protests, one lay leader told the Register-Leader, the forerunner of UU World, that “Selma may redeem the Unitarian Universalist movement.” But redemption didn’t come easily. “We had a great consensus,” recalls the Rev. Ed Harris, the chair of the Selma memorial committee, “but within a very short period of time, things that had united us divided us.” The moral clarity of Selma—with its martyrs, its prophetic leader, its focus on constitutional rights—disappeared in the late sixties. UUA President John Buehrens says that “many of the association’s hopes embodied at Selma were crushed,” as the Vietnam War, the assassination of King, the black empowerment controversy, and the UUA’s financial crisis in 1970 exhausted and disheartened Unitarian Universalists.

But our relationship to the past shifts. Perhaps we are far enough away from the events in Selma to remember them safely. Or perhaps, as the Rev. Jack Mendelsohn says about the UUA’s current anti-racism initiative, “It’s taken us all these years to get back on track.” The Rev. Clark Olsen, who survived the attack that took James Reeb’s life, says that 20 years went by before his thoughts about Selma began to mature. His reflections conclude our coverage. The Rev. Orloff Miller, who was also with Reeb, hopes the UUA’s new monument will help us remember—and prod us to act. He says he has been inspired for 36 years by writer Hermann Hagedorn’s words: “We must do a harder thing than dying is. We must think! and ghosts will drive us on.”

On March 11, 2011, 46 years after Reeb’s death, the Anniston Star reported that the FBI is investigating the case. On May 20, 2011, the FBI closed the case again.

Related Stories

- Timeline of the Selma civil rights campaign

- Martin Luther King Jr.’s previously unpublished eulogy for James Reeb (May/June 2001; PDF)

- Listen to Martin Luther King Jr.’s eulogy for James Reeb. Recorded in Selma, Alabama, by Carl Benkert on March 15, 1965.

- Memoir of King’s eulogy for James Reeb

- Witness to Reeb’s death looks back

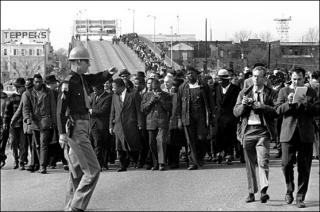

Civil rights demonstrators, including the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and 450 religious leaders, stream across the Edmund Pettus Bridge on March 9, 1965. (AP File Photo)

Corrections

Earlier versions of this article spelled Jimmie Lee Jackson’s name “Jimmy,” following the lead of many historians. We have updated the spelling to reflect his family’s preferred spelling.