Advertisement

One of the largest Unitarian Universalist congregations in the United States has put racial justice at the center of its mission, with members risking arrest and fines to support the Black Lives Matter protests in Minnesota.

But First Universalist Church of Minneapolis is only part of a larger group of UU congregations in the Twin Cities area that is championing racial justice. Hundreds of UUs, including 20 UU clergy, joined in a major demonstration organized by Black Lives Matter at the Mall of America in December, and the clergy have signed a letter asking the city to drop criminal charges against demonstration organizers—or to charge them, too.

For the past two-and-a-half years, First Universalist Church has been focused on “a racial justice journey,” working to deepen “our understanding of race, racism, and whiteness,” said the Rev. Justin Schroeder, senior minister of the 951-member congregation.

“It’s a core identity of the church, and if you’re part of this church, the expectation is you’ll come into this conversation,” said Schroeder, who has organized his fellow UU clergy in the area on several recent actions.

Schroeder and some congregants participated in the December 4 shutdown of Interstate 35, organized by Black Lives Matter to protest the grand jury decisions in the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner. The church held a Black Lives Matter vigil one week later that drew a racially diverse crowd of 400 people. But Schroeder said the congregation’s racial justice journey is woven into every aspect of church life. The church appointed a Racial Justice Leadership Team, created a curriculum for parents to discuss issues of race with their children, and held training sessions on racial awareness for board members, staff, lay leaders, and others.

“It’s really articulating the sense that our faith is fundamentally a faith that claims that everyone matters and we are in this together,” said Schroeder. “That theological claim is incompatible with racism.”

This work put the congregation on strong footing when about 25 members of the church participated in a peaceful demonstration for racial justice at the Mall of America in Bloomington, Minn., that drew between 2,000 and 3,000 protesters. Several hundred of the protesters were UUs, estimates the Rev. Meg Riley, senior minister of the Church of the Larger Fellowship, a UU congregation “without walls,” who herself was there.

Of the approximately 40 clergy who were part of the demonstration, at least 20 were UU ministers from the Minneapolis–St. Paul area, said Schroeder, who attended with his wife and their six-year-old son.

The demonstration was organized and led by young people of color connected to Black Lives Matter, who, at the invitation of First Universalist Church, held a training at the church for about 40 people. The leaders told the group that mall authorities would make several demands that the protesters disperse. At the third demand, leaders said they were to disband. They said there was no intention to provoke police or to have anyone arrested, according to Schroeder.

Schroeder said an important aspect of the training was for the predominantly white group of trainees to learn to follow the instructions of the organizers. “In doing that, these trainers told us, you begin to dismantle and subvert white supremacy. In trusting the leadership of young people of color, you upend the model that white ideas are better ideas,” he said. “That helped me as a person of faith feel really grounded, that I’m there in deep solidarity with the organizers who have a vision and plan. And part of that is, [the protest] needs to disrupt business as usual, to be in the Mall of America to say, in a public square, ‘We’ve been trying to solve this problem for decades.’”

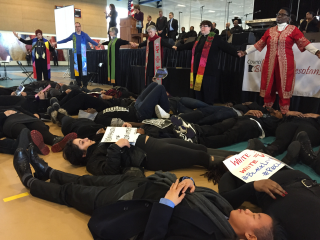

On December 20, during the final shopping weekend before Christmas, thousands of protesters lay on the floor in the rotunda of the mall in a “die-in,” while the clergy in their vestments stood around them praying, “essentially memorializing and remembering the bodies that have died at hands of police violence in past decades,” said Schroeder.

Although by all accounts the protest was peaceful and shoppers were not impeded from getting to stores, dozens of stores shut down and scores of police clad in riot gear appeared. According to media reports, plainclothes police had attended planning meetings, and mall officials had asked that the protest be held outside. The city’s position is that the mall is private property and unauthorized demonstrations were illegal.

“I feel like police overreacted,” Schroeder said. “Organizers were clear from the beginning that this was a nonviolent event trying to raise awareness. No property was damaged, no one was hurt.”

At the third demand by authorities to disband, they did so, gathering outside to continue singing.

Nonetheless, 10 people who helped organize the protest—known as #MOA10—were later charged with trespassing and other crimes, including Riley’s child, Jie Wronski-Riley, 18. Another 25 people were arrested at the demonstration. City officials are hoping to force protesters to pay thousands of dollars for police overtime and other expenses related to the demonstration.

Spokespeople from Black Lives Matter and civil rights lawyers are condemning the city’s actions against the protesters. About 40 clergy who attended the protest wrote a letter to mall managers and city officials emphasizing the peaceful nature of the protest and asking that they be charged, too, if the charges against the #MOA10 aren’t dropped.

“We said that we helped organize that, that I had invited the organizer to hold the training at our church,” said Schroeder, “and that thousands showed up to make this a peaceful event.” He has spoken on the radio several times about the fact that faith communities were involved in the protest and that many had invited congregants to join. The letter has generated ongoing conversation and kept Black Lives Matter in the news, he said, but neither mall officials nor the city attorney has responded directly to the letter.

In the meantime, First Universalist Church will continue its antiracism work, Schroeder said. “Every 28 hours a person of color dies at the hands of the police or security personnel or vigilantes, but now I’m awake and starting to see that, I cannot and will not remain silent.”

“The message is really that business as usual has to be disrupted, we have to restore our collective humanity, we have to find a way to end this racial nightmare that’s not as overt as cross burning but is still impacting and killing people.”

Photograph (above): Twin Cities–area UU ministers join interfaith colleagues to form a prayer circle around young adults staging a Black Lives Matter die-in at Macalester College on Martin Luther King Jr. Day. The City of Bloomington, Minnesota, is pressing charges against the same activist group for a December 20 protest inside the Mall of America. (© Jerry Holt / Star Tribune / Minneapolis-St. Paul 2015.)