Advertisement

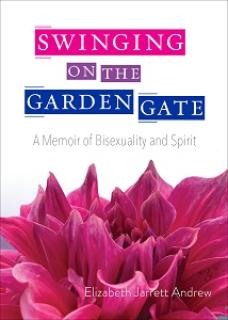

The following is an excerpt from the recently released Swinging on the Garden Gate: A Memoir of Bisexuality and Spirit, 2nd edition (Skinner House, 2022), the Justice and Spirit: Unitarian Universalist Book Club selection for June.

Every story begins with a word: a daunting word, a word that mars the blank white page or inks the air.

A word has upright bones and sinews; it is created the way a body is created—from dirt and spit. It walks about relating to other words until it is a part of an extended thought or metaphor or entire narrative telling how the world began. The world began in chaos, like a rough draft. It began with the faith that creation is good.

Once I carried within me a word so potent that it spread through every artery and vein until my tongue swelled with silence. I carried it into the faculty lounge at a middle school where conversation ranged from marriage to the two-car garage. The word sat rock hard in my stomach, beside the cafeteria lunch I wolfed down in twenty-two minutes. I carried it with me through the corridors, where one student called another queer and sent me raging, dragging him into the classroom by his shirt sleeve. Angled against the blackboard, arms crossed, he defied me with his eyes. My red-faced fury didn’t go far; I forced down the real word and ranted instead about inappropriate behavior and put-downs. I carried it with me through three years of semester reviews with my principal, as we hassled over the inclusive range of paperbacks on my classroom shelves. She was always cordial. The books that passed muster were those that didn’t make any waves. Sitting before her wide desk, the boundaries of my body became retaining walls while inside raged the tidal wave of a word.

I carried my word into Sunday worship with a liberal congregation in the heart of Minneapolis. Adult education that morning was a panel discussion on bisexuality; should the church’s statement of intentional welcome include bisexuals alongside gays and lesbians? My eyes widened as several people described their experiences of being drawn to men and women and made a case for celebrating the expansive diversity of God’s creation. The word inside me turned restless and eager. I wanted to grow on my spiritual journey—to move forward after years of stasis—and I had a hunch that speaking my word would set me in motion.

I was terrified. Coming out in any form cracks the world open. When we come out, we take a buried truth, an inward reality residing near the soul, and pull it to the surface where it wreaks havoc on every perpetuated falsehood. We yank a piece of our essence out into the air, transforming in the process the self we thought we were as well as the community around us. I came out bisexual, claiming with pride God’s presence in the unique desires of my body. But as soon as I could recognize incarnation within my own skin, it was everywhere else as well—in my past, in the landscape, in each object, in the story itself. . . . The middle school where I taught seventh-grade English couldn’t accept my word, but (thank heavens!) my church did, and now the religious contingent marching in the Pride Parade is one person larger. Where the word is spoken, the huge creaking wheels of creation begin to turn.

Swinging on the Garden Gate: A Memoir of Bisexuality and Spirit, 2nd edition (Skinner House, 2022)

InSpirit UU Book and Gift Shop

What stuns me is how the word of God resides in each of us, carved into our very cells. I was taught to look for the word in the Bible, whose onionskin pages seem holier than those of a paperback novel and whose well-worn language we like to associate with the voice of God. After I came out, scripture tumbled down from the pulpit. It never belonged there in the first place: the word became flesh (not with Jesus, who simply reminds us of this fact, but in the very beginning) and it dwells among us, full of grace. When I sink into the sensual and relentless truths of my sexuality, and find there, hidden in the sticky recesses of my sex where I least expect it, holiness, it seems to me that all of creation’s bones and blood, vapor, soil, feathers, and solidity are infused with a sacred word. God is thoroughly, unabashedly incarnate. The spiritual journey is so physical that it makes me shiver. It sends me running barefoot on deer paths through the woods, and it shakes me awake during the blackest part of the night.

There are as many scriptures as there are stories told with integrity. The word of God inhabits our lived stories, the ordinary way our days unfold, and it inhabits the craft by which we give our stories form. Swinging on the Garden Gate is my attempt to recognize that spark of spirit embedded in the solid matter of my life—in childhood, in coming out bisexual, in encounters with death and loss and wild growth—with the hope that my journey might be an invitation for others to do the same. The word comes alive when we claim what is sacred (life-giving, fundamental, charged with mystery, and frightfully beautiful) within our stories. This is how we become the word, moving about in the world. We breathe in deeply, down through the lungs and diaphragm to the core, and then release that intimate mingling of air and vibrating flesh into speech. We voice a truth. We create, and in so doing participate in our own creation.

I hunger to hear sacred stories. As a gift to encourage others, I offer my own.