Advertisement

Calligrapher Margaret Shepherd in her Boston studio. (© 2002 Dennis Paiva)

We treat the letters of the alphabet as tools, and why wouldn’t we? Used the right way, they get our point across. Schools may have given up on teaching penmanship—after all, most of us don’t really write any more, we just type—but the letters we use today, even on computer screens and inkjet printers, are modeled on handmade objects: a shape made by pen and ink, or carved into stone with a chisel. Some people see the alphabet as more than a toolbox, however. Calligraphers transform these everyday tools of communication into things of beauty. Simonides said, “Painting is silent poetry, and poetry painting that speaks.” For master calligrapher Margaret Shepherd, all manner of words become painting and poetry.

“Writing is really an extension of gesturing—a way to make a motion visible, memorable, and lasting,” Shepherd writes in Learn Calligraphy, the new edition of her best-selling introduction to the art. Her memorable gestures are everywhere on display at First and Second Church in Boston, her Unitarian Universalist congregation, where her ink-on-paper memorials to the church’s illustrious members and ministers testify not only to a remarkable history but to the power of an ancient yet modern art. They are on display as well in UU congregations across the continent, in silk-screened posters of the Seven Principles that she lettered in 1986, shortly after they were adopted.

When the First Church’s 100-year-old downtown Gothic sanctuary was destroyed by fire in 1968, the congregation turned to a controversial modern architect to design its new home. Paul Rudolph was famous for designing austere concrete buildings that looked nothing like the old Victorian church. The Unitarian congregation had looked to medieval architecture for inspiration in 1868, but now they looked resolutely ahead.

The church tower survived the fire, so Rudolph left it standing, along with the eastern porch. The charred frame of a rose window rises above it, empty and open to the sky. Facing this side, what you see is a ruin; walk around the corner and you find that the ruin serves as one wall of an unmistakably modern building, angled and turned on edge.

Margaret Shepherd fell in love with the building immediately. Its bare, striated concrete walls mystified some parishioners, but Shepherd saw something familiar. “It was so easy to draw! You just take a pencil,” she told me, gesturing toward the walls. I quickly saw what she meant: Hold a pencil sideways, and you can recreate the texture of these walls with simple strokes.

“One of the things about a work of art is that it inspires other artists,” she said. “This building was just a shot in the arm. It turns into not just a canvas but a piece of paper. Pencil marks! It’s a handmade drawing turned into a building!” The angles in the building? Shepherd sees folded paper, like origami. “It’s very controlled and disciplined,” she said, “but it’s also funny and very creative.”

Her tribute to a renowned architect also describes key features of her own art, which appears in more than a dozen books about calligraphy as well as in some 60 memorials that line the walls of the sanctuary and a smaller chapel.

She created most of the memorials in the early 1980s to replace the stone, wood, and bronze monuments destroyed in the fire. From photographs, Shepherd knew what the original monuments had said and how they looked. But she had no intention of producing copies: the congregation had commissioned modern memorials for their new building. Instead, she studied the memorial texts and learned about the individuals, looking for ways to present their lives with simple, modern designs. And the collection keeps growing, perpetuating a tradition in a congregation that is centuries old.

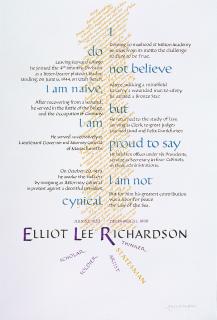

The newest memorial, unveiled last year, commemorates Elliot Richardson, a longtime church member who died on New Year’s Eve, 1999. Richardson held four cabinet positions in the Nixon and Ford administrations, more than any other person in U.S. history, but he is remembered chiefly for resigning as attorney general rather than carry out President Nixon’s order to fire the special prosecutor investigating the Watergate burglaries.

Margaret Shepherd’s latest memorial honors longtime church member Elliot Richardson (1920–1999), remembered chiefly for resigning as U.S. attorney general rather than carry out President Nixon’s order to fire the special prosecutor investigating the Watergate burglaries. (© 2001 Margaret Shepherd)

For Richardson’s memorial, Shepherd collaborated with the person who had invited her to begin the calligraphy memorials project almost 20 years ago. Richardson’s brother, Dr. George Richardson, a church trustee, had seen her work in a Boston gallery. “He liked the way my work looked,” she said. “There are a lot of calligraphers who could do a memorial plaque in the old style, but that’s not my specialty. I like pushing the edge.”

George Richardson wrote the citation for his brother’s memorial and he and Shepherd selected two quotations from his writing. “I thought about him a lot,” Shepherd said. “This wasn’t an easy design. It looks inevitable, but that means it took a lot of drafts.” Below his name are five epithets: scholar, soldier, artist (he was known as a cartoonist and perpetual doodler), statesman, and thinker. “There was a point at which he would go at an angle to what was happening. That’s the statesman”—the only epithet written with yellow ink rather than violet—“and that’s at an angle to the grain of his life. I wanted a sense of crucible somewhere in here, and a ray of light coming in, hitting the colors.”

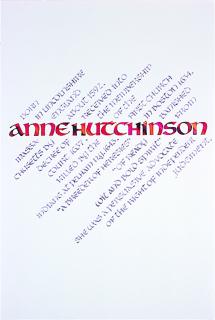

Because the congregation is one of the oldest in the United States—it was founded immediately after the city, in July 1630—it has had its share of statesmen and rebels, like John Winthrop, the Puritan governor of the original Massachusetts colony, or Anne Hutchinson, the woman tossed out of the 17th-century church and banished to Rhode Island for challenging the minister’s interpretation of the Bible. Because the Puritans were dissidents, Shepherd made her memorials for the original members of the church asymmetrical and non-rectilinear. She also reproduced the effect of the striated concrete with gray ink, linking the earliest members to the congregation’s most modern building. The odd angles of the text reveal not only the original Puritans’ adventurousness, but echo the building’s unusual angles, too. In subtle and beautiful ways, Shepherd has linked more than three and a half centuries of complex history, audaciously joining modern Unitarian Universalists to their unlikely ancestors, the infamously dour Puritans.

Anne Hutchinson challenged the Puritan ministers’ interpretation of the Bible and was banished, fatefully, to Rhode Island. “She set everybody on edge,” says Shepherd, who commemorated the independent thinker with angled text. (© Margaret Shepherd)

The memorial for Charles Chauncy (1705–1787), minister for 60 years during the tumultuous 1700s, reflects his reputation. Unmovable and steadfast as his congregation’s meeting house, Chauncy came to be known by the building’s nickname, “Old Brick.” So Shepherd wrote his memorial using square letters. She described the block-like memorial as “stubborn and contrary,” adding, “No way did he have a graceful style.” Chauncy gradually led his Puritan congregation to the threshold of Unitarianism, so the memorial is black on the top and gradually shifts to red at the bottom.

“You can say a lot with the letter design,” she explained. “I don’t use ornament much at all. This is my manifesto about what calligraphy can do.”

Some of the original monuments include epithets from a distant era: “John Davenport. Preacher. Writer. Colonizer. Leader. Theocrat.” Shepherd let the words speak for themselves when she wrote his new memorial. “It’s harder to capture a likeness of a grim, old white guy,” Shepherd said. “A portrait painter or a photographer has the same problem. But an opera singer! It’s a lot easier to deal with a poet, or a woman, or someone with a colorful story—the person backing a lost cause rather than the guy in power. I know which side I’d be on. I’d definitely be with the agitators and rock-the-boat people,” she said.

Creating the First and Second Church memorials forced Shepherd to think about the larger meaning of memorial art. “Who goes on the wall? How do you pick these people?” she asked. “Everybody’s terrified that you’ve got to have someone famous. They’ve got to be important enough—and then, you’re back in old England and you’re back in the Episcopal Church and you’re back in the Establishment.”

Shepherd will have none of it. She grew up in Ames, Iowa, where her father Geoffrey had helped found the Unitarian Universalist Fellowship in the 1950s. “That was eight folding chairs in the basement of the Y,” she said. “Then I came out here, and there’s a minister in robes, and hymnals, and, O my God, I couldn’t believe my eyes! I’m from the Midwest,” she explained. “I’ll give you an earful about prairie Marxism, because when you come to Boston from the rest of America, it looks pretty elitist. It really does.

“So I took the UUA’s First Principle, the dignity of every person, and I thought—every person should be up” on the wall. She led me toward the eastern wall of the sanctuary. Tucked into the concrete striae were thin ribbons of copper. On each strip was a person’s name: the names of church members, literally embedded in the walls. The effect is subtle and exquisite. “To me it’s the natural outcome of the building and the denomination,” Shepherd said. She began with the 300 names of the congregation’s current members. “I’d like to do the entire membership from day one”—371 years ago—“which would be about 4,000 names.”

She keeps looking for ways to enhance her congregation’s relationship to its building by putting more of its words into the building. “Young people write their own statements for the Coming of Age ceremony,” which they present to the congregation. “Well, I sat there listening to them, and bing! Why not put them on colored strips? Somewhere where they don’t stay up forever, maybe, or just one sentence, but there you are: There’s words that the church is made of.”

Shepherd’s latest book, The Art of the Handwritten Note: A Guide to Reclaiming Civilized Communication, marks a departure for her. Her 14 earlier books have introduced thousands of readers to the art of calligraphy—a passion she discovered in college—but her new book is a reminder that a simple ballpoint pen can produce something with unusual value, too. “When you write a letter to someone by hand,” she said, “you speak with a different voice. It opens up something you don’t get very well in any other way.” Why does a handwritten note stand out with peculiar force?

“There’s a reverence for the handwritten word,” Shepherd said. “People know that a human put a lot into it. They just don’t respond the same way to print.”

Surprisingly, Shepherd said she is not a natural penman. “I flunked writing in third grade,” she said. “I was artistic but I could not write to save my life! It doesn’t come naturally. So I’ve overcompensated.”

For those who have learned to see the beauty tucked away in the toolbox of the alphabet through her infectious advocacy, Margaret Shepherd has done much more than overcompensate for poor elementary school penmanship. She has made an ancient art immediate, intimate, and fully modern.