Advertisement

In 1969, the Unitarian Universalist Association held its General Assembly at the Statler Hilton in Boston, which is now the Park Plaza Hotel. During the 1940s the only man of African descent you would have seen at their annual meeting was Egbert Ethelred Brown. But 1969 was completely different. Most delegates had never seen so many black UUs—unless they had been in Cleveland for the General Assembly the year before. This black presence left many white UUs perplexed. Some even asked, “Where did they all come from?”

In “The Empowerment Tragedy” (UU World, Winter 2011), Mark Morrison-Reed describes the conflict over funding black power groups that led to a walkout by many black delegates and their white supporters.

New England, home to more UU delegates than any other region of the United States, was more provincial fifty years ago than it is now. But UU reality was different than many believed it to be. Consider this list of names. Do you know them and what they did?

Errold D. Collymore in White Plains, New York. Margaret Moseley at the Community Church of Boston and the Unitarian Church of Barnstable, Massachusetts. Nathan J. Johnson in Seattle. Joseph H. Jenkins in Richmond, Virginia. Cornelius W. McDougald and Isaac G. McNatt at the Community Church of New York. James F. Cunningham in Sitka, Alaska. Harold B. Jordan at All Souls Unitarian Church in Washington, D.C. Cornelius Van Jordan in Cincinnati. Selina E. Reed and Kenneth L. Gibson at First Unitarian Church in Chicago. Jim Bolden in Philadelphia. Sylvia Lyons Render in Durham, North Carolina.

All are African Americans, and all served as head of the governing board of a predominantly white UU congregation during the 1940s, ’50s, or early ’60s. In 1956 a survey reported that eighty Unitarian congregations had African American members, and in forty-nine of those congregations African Americans were active as officers. That means sixty years ago nearly 10 percent of Unitarian congregations had African American members holding positions of leadership.

This is not common knowledge, be it 1969 or 2017.

What is the consequence of not knowing? We see the lack of black leaders confirming the belief that Unitarian Universalism does not appeal to African Americans. Why don’t we know this history? Why would we, when in the context of Unitarian Universalism, and across the entire American milieu, black lives don’t matter?

The consequence is that we have embraced a false narrative about who we are.

In 1979, ten years after the 1969 General Assembly in Boston, almost no scholarship existed about African Americans in Unitarian Universalism, and some of what had been written was inaccurate. Freedom Moves West: A History of the Western Unitarian Conference, 1852–1952, mentions the founding of the Free Religious Fellowship, a largely African American congregation on the South Side of Chicago, but mistakenly identifies Euro-American Kenneth Patton as one of its organizers. In A Stream of Light: A Short History of American Unitarianism, published in 1975, there are two sentences about Egbert Ethelred Brown. That was it.

Freedom Moves West designates Celia Parker Woolley and her husband as founders of the Fredrick Douglass Center in Chicago, but fails to mention its African American cofounder Fannie Barrier Williams. In Two Centuries of Distinguished UU Women, published in 1973 by the UU Women’s Federation, not one African American woman is included among the 102 biographies—not Williams, not Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, not Florida Yates Ruffin Ridley. Their biographies did not appear in a UU publication until Dorothy May Emerson’s Standing Before Us, in 1999.

African Americans were invisible in our scholarship. Their absence reflected the belief—and contributed to the belief—that there was no story to tell. Yet African Americans had been founding members of Universalist, Unitarian, and UU congregations as early as 1785, when Gloster Dalton was a signatory at the founding of John Murray’s Universalist congregation. Other founding members include Amy Scott, one of the incorporators of First Universalist Society in Philadelphia in 1801; Lewis Latimer, a founder in Flushing, New York, in 1907; James Cunningham, the first president of a fellowship in Sitka, Alaska, in 1955; and Sylvia Lyons Render, a founding member of the Eno River Congregation in Durham, North Carolina, and its first board secretary. With one exception, these congregations—all predominantly white—still exist.

David Whitford tells the story of how a Cincinatti UU church reached out to the family of the black Unitarian minister it had rejected decades before, in “A Step Toward Racial Reconciliation” (UU World, May/June 2002).

A step toward racial reconciliation

There were other UU congregations that black folks founded, or at least tried to found. In 1860 William Jackson, a Baptist minister, testified at the Autumnal Convention of the American Unitarian Association (AUA) to his conversion to Unitarianism. “They took a collection and sent him on his way,” historian Douglas Stange writes. “No discussion, no welcome, no expression of praise and satisfaction was uttered, that the Unitarian gospel had reached the ‘colored.’”

In 1887 John Bird Wilkins founded the Peoples Temple Church (Colored Unitarian) in Chicago; it lasted about a year. In 1892 Joseph Jordan founded a Universalist congregation in Norfolk, Virginia. Thomas Wise founded others in Suffolk and Ocean View, Virginia, in 1894 and 1902. Egbert Ethelred Brown started a Unitarian congregation in Jamaica in 1908 before moving to Harlem in 1920, where he founded the Harlem Community Church; the AUA provided sporadic financial support, then took away his ministerial fellowship in 1929. Can you imagine how we would be enriched today if there was a vibrant UU congregation in Harlem that had been around for almost 100 years? In 1932 William H. G. Carter founded a church in Cincinnati, but the white ministers in the area did not tell the AUA of its existence. In 1947 Lewis McGee was among those who founded the Free Religious Fellowship in Chicago; today it is only a remnant. None of the other congregations survived.

Suppose that funds had been forthcoming in 1911 when Joseph Fletcher Jordan asked Universalists to support plans to add a seminary to the African American school he ran in Suffolk, Virginia. The graduates might have fanned out across the South to preach the gospel of the larger hope, God’s all-embracing love. They needed $6,000 for this endeavor. Jordan traveled around the Northeast in 1911–1912 raising money, but in the end raised less than $1,500. To put this in context, in April 1890, the Universalists began a mission in Japan. The Japanese mission was given at least $6,000 a year, often more, eventually totaling more than $275,000. During the same years the Universalists could not raise $6,000 for their “Mission to the Colored People.” What does it suggest? Black lives don’t matter.

Imagine if Jackson had brought his Baptist congregation into the AUA or if Jordan had been successful in establishing a seminary. I cannot help but wonder what our worship would have been like. What gets emphasized when a black Universalist preaches about God’s enduring love? Likewise, what is highlighted when a black Unitarian preaches about freedom?

In UU worship and liturgy, as in our scholarship, African Americans did not exist. There was nothing by or about African Americans in UU hymnody. In 1937 there was nothing in Hymns of the Spirit, with the exception of the Civil War anthem “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” In 1955 the children’s hymnal We Sing of Life included two spirituals. There is nothing at all in Hymns for the Celebration of Life, which was published in 1964. How Can We Keep from Singing?—published in 1976, and not by the UUA—included “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” “We Shall Overcome,” two spirituals, and “De colores.” Not until Been in the Storm So Long was published in 1991 did a collection of readings by black UUs exist. Not until 1993, with the appearance of Singing the Living Tradition, did African American culture make a significant appearance in a UU hymnbook.

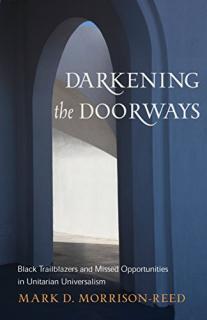

Read Darkening the Doorways: Black Trailblazers and Missed Opportunities in Unitarian Universalism, ed. by Mark Morrison-Reed (2011), and Black Pioneers in a White Denomination, by Morrison-Reed (1992).

inSpirit UU Book and Gift Shop

A 1989 study of UU worship preferences tells us that African Americans don’t fit the UU pattern. What was most important in worship for 74.5 percent of UUs overall was “intellectual stimulation.” What was most important for African American UUs who responded to the survey? “Celebrating common values” (chosen by 69 percent), then “hope,” “vision,” and “music”—all before “intellectual stimulation.”

Why did African American culture, experience, and sensibilities remain invisible?

There was cultural dissonance between a people who, having political rights, prized “intellectual freedom” in their struggle with orthodoxy and those for whom the struggles for basic freedoms—political and spiritual freedom—were paramount. But the white conscience does not want to know. Not knowing the history and not being reminded during worship means white liberals don’t have to feel guilty or be confronted by the emotional aridness of UU worship.

Another example of how little regard we had for African Americans: When the Universalists balked at supporting the mission in Suffolk from its general fund, Universalist Sunday schools raised money to support Jordan’s efforts. Offerings totaled $440 in 1917; that rose to $950 in 1919. Between 1918 and 1921, however, Universalists gave $75,000 to aid Armenian war victims, as well as supporting the mission in Japan. Why was helping those far away more compelling than reaching out to those nearby? What does it tell us? Black lives don’t matter.

Turn to religious education. When in 1968 Hayward Henry, the chair of the Black UU Caucus, claimed that “nowhere” in UUA religious education curricula were black contributions to American society studied, the charge was somewhat hyperbolic. Go through the New Beacon Series that ran from 1937 to the early ’60s and it’s true: there is little. When Church Across the Street was revised in 1962, it included one paragraph about the African Methodist Episcopal Church, but did not mention that its founder Richard Allen was supported by Universalist Benjamin Rush. In 1965, as the New Beacon Series was ending, Sophia Lyon Fahs devoted four chapters in Worshipping Together with Questioning Minds to the life of George Washington Carver. In addition, for decades dating back to 1917 the Universalist General Sunday School Association used the American Missionary (later Friendship) Program to highlight the Suffolk Mission and race relations, which prompted many individual gifts of money or books and other useful items. What Henry said was true but not quite complete. Still, the New Beacon Series provides yet another example of black invisibility: a falsehood perpetuated by what we taught our children. The unspoken, hidden curriculum was: black lives don’t matter.

During the black power era an effort was made to address the issue of racism through religious education. Black America/White America: Understanding the Discord was the never-published result. The trouble was the author, who insisted on working in isolation, produced a book rather than a curriculum. It was reported to be moving, but it was long—1,000 pages—didactic, inappropriate for children, and expensive to produce. Here was “intellectual stimulation,” our highest professed value, at its most oppressive, in black hands, killing the life of the story. When this pedagogical disaster wasn’t published some called it racism. What I see are liberals fearful of being accused of being racist holding their tongues instead of saying this cannot possibly work.

The UUA Religious Education Department’s efforts then produced Africa’s Past: Impact on Our Present in 1976 and Adventures of God’s Folk, with sessions about Sacajawea and Harriet Tubman, in 1978. But no systematic approach to the inclusion of African American UU history took place until the UU Identity Curriculum Team was established in the mid-1980s. By 1993 it had produced a half dozen curricula in which black history was entwined with the stories of other UUs.

Despite the invisibility of black lives in our curricula, African Americans continued seeking a home in Unitarian Universalism. In 1920, for example, 10-year-old Jeffrey Campbell discovered Universalism and on his own began attending First Universalist Society in Nashua, New Hampshire, bringing his little sister along. In 1929, Campbell enrolled in the theological school at Saint Lawrence University, a Universalist seminary. Fifty years later, Campbell told me that when he was admitted to the seminary, the superintendent of the New York State Universalist Convention complained to the dean, John Murray Atwood, “Why are we wasting the denomination’s money on a nigger?” Campbell graduated in 1935 but the Universalists could not find a congregation willing to settle him, nor, in 1937, could the Unitarians. The same was true for Lewis McGee when he approached the AUA in 1927, Harry V. Richardson in 1930, Eugene Sparrow in 1949, McGee again in 1956, David Eaton in 1959, and Thom Payne in 1970.

Imagine. What if a congregation had been eager to settle Campbell? Of mixed race, he was raised in New Hampshire by his white mother. This was not about culture. He would not have offered a radical departure from the New England ethos. This was pure and simple racism.

The fact is this: The person who controlled Universalism’s journal, the Christian Leader, for twenty-two years was an out-and-out racist. John van Schaick was the only Universalist leader to argue against starting a seminary in Suffolk; earlier he argued for closing the Suffolk mission altogether; he agreed with the Daughters of the American Revolution when it refused to allow Marian Anderson to sing at Constitution Hall; when he became editor of the Leader, articles about the Universalist “Mission to the Colored People” disappeared from the front page; and he said Jeff Campbell was betraying his race and “should go elsewhere” if he wished to be a minister.

Are you confused? This faith that you love has said over and over, sometimes in word but more often in deed: black lives don’t matter.

In America, at least, liberal religion was wedded to Anglo-Saxon culture. There was no doubt in William Ellery Channing’s mind or Theodore Parker’s mind of their own superiority. They believed, as did Sam Eliot and Louis Cornish after them, that the New England (which is to say, Yankee) Unitarian frame of mind was something to be promulgated across America. From this racialist point of view blacks ranked below the Irish and the Slavs.

From the vantage of the twenty-first century it is easy to call them all racists, particularly van Schaick. But his editorship, which did not begin until 1923, had nothing to do with the Universalists sending hundreds of thousands of dollars overseas while raising only a pittance for Suffolk. The money trail does not lie, nor does the settlement record of the Unitarians and Universalists. The behavior of both was imbued with prejudice, and their racism was systemic. A harsh judgment, but better that than perpetuating the assumption that Unitarians and Universalists were enlightened when they were not.

What does this have to do with us? It is our inheritance and controls us in ways we cannot imagine. However, simply calling them out offers little illumination. What we need is to understand—for understanding might help us make different choices today.

Why? Why? Why was it so? My answer is: Location. Location. Location. Class location. Geographic location. Theological location.

First, class location. You have heard that the Unitarian Channing would not condescend to speak to the Universalist Hosea Ballou. In Boston and Massachusetts, Unitarians in the nineteenth century were the Harvard educated elite. Universalists were not. Philip Giles, last president of the Universalist Church of America, said (after describing it as an oversimplification), “The Unitarians were urban, well educated, used to money, used to power and its wise use. The Universalists tended to be rural, less well educated, fearful of power, and not used to it.”

This adds an interesting, and unexpected, twist to this story. In appealing to African Americans, class location was actually an advantage for the Unitarians and a disadvantage for the Universalists.

Some Unitarians belonged to a progressive intellectual strata that included a handful of black intellectuals. Author and abolitionist Frances Ellen Watkins Harper was a Unitarian in Philadelphia. Abolitionist Frederick Douglass attended All Souls Church in Washington and All Souls Church in Chicago, where African American activist Fannie Barrier Williams was a member. New Bedford, Massachusetts, merchant and Unitarian S. Griffiths Morgan paid for Booker T. Washington’s education at the Hampton Institute; Washington was later a guest speaker at Harvard Divinity School and Meadville Theological School, Unitarian seminaries. At First Unitarian Church in Rochester, New York, Hester C. Whitehurst Jeffery was an intimate of Susan B. Anthony. John Haynes Holmes was on the founding board of the NAACP with W.E.B. Du Bois. Homer Jack was a founder of the Congress of Racial Equality with James Farmer and Bayard Rustin. Child psychologist Kenneth Clark was a member of Community Church of New York. Whitney M. Young Jr., the executive director of the National Urban League, became a Unitarian in Atlanta; his sister, Professor Arnita Young Boswell, was a member of First Unitarian Church of Chicago.

These are highlights. An exhaustive list would include Arlington Street Church in Boston, where the editor of the local black newspaper and the executive director of the Boston Urban League were members, and First Unitarian in Chicago, where two managing editors of Ebony magazine and a state senator were members. I have compiled a list of 100 African American UU laypeople born prior to 1930—doctors, dentists, academics, teachers, scientists (two worked on the Manhattan Project), social workers, lawyers, and activists—and in almost every case they were Unitarians, not Universalists.

Given the middling class location of most Universalists, there were few venues in which they would have come into contact with black intellectuals. Without that exposure and interaction many Universalists seem to have embraced the pervasive American, white supremacist attitudes about African Americans, and those were reinforced by the editor of the Universalist Leader. Black lives didn’t matter.

Second, geographic location. Phil Giles also said the Universalists tended to be rural. Universalists were strongest in places in which there were few African Americans. Universalism started in New Hampshire, the eastern seaboard, and Pennsylvania, and in the nineteenth century spread into small town New York, then into the Midwest, North Carolina, and finally into the deep South.

New England—except for Roxbury and Dorchester—was white, white, white. How white? In 1970, across the American birthplace of Unitarianism and Universalism the percentage of African Americans in the population was minuscule. In Vermont, Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts it was 0.2, 0.3, 0.3, and 3.1 percent respectively.

As Unitarianism and Universalism moved beyond their homeland, Universalism in particular took root in the rural and small town Midwest, which was white, white, white. When millions of African Americans surged North between 1910 and 1940 during the Great Migration, they followed the railroad lines. From Mississippi and Arkansas, they came to Saint Louis, Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland; from Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina, they came to D.C., Baltimore, Philadelphia, Newark, New York; from Texas they went west to Los Angeles. These major urban areas in which the migrants settled were not Universalist havens. And when Universalism had a presence in a city and blacks moved in, the middle-class white Universalists moved out, as did many Unitarian congregations. The list of UU congregations that fled to the suburbs is long.

Nonetheless, in 1956 eighty Unitarian congregations reported having African American members. In 1963 one UU congregation was one-third black and two others claimed to be 10 percent black. They were in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles. Unitarian congregations in D.C., Cleveland, Detroit, Cincinnati, and Philadelphia chose to remain in the city center—and they became substantially integrated, including the black lay leadership with which I began.

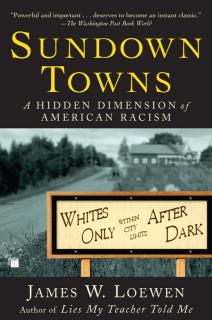

James W. Loewen, author of ‘Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism’ (2006), describes his research on hundreds of U.S. towns that formally or informally excluded black residents into the 1970s in ‘Was Your Town a Sundown Town?’ (UU World, Spring 2008).

In the more out of the way locations it was not only that there were no African Americans, but the nature of small towns and rural areas kept people apart. In them, black and white, rich and poor are clannish and insular. And small towns would have been sundown towns.

Alongside geographic isolation, Universalism had an additional problem. Having been in decline for a half century, Universalists were more worried about survival than about outreach to African Americans. As Gwendolen Willis, the daughter of Olympia Brown and president of the congregation in Racine, Wisconsin, wrote in 1954: “As for negroes, they could be members, but would not be called to fill our pulpit as that would further complicate our foremost problem, that of survival.”

Unitarians, and to an even greater degree Universalists, and African Americans inhabited different worlds. Outside urban pockets there was little contact, and when there was we can assume the African American was in a subservient role.

Third, before I take up the question of the theological location you must set aside your twenty-first century Humanist frame of mind for a theistic one.

Since there was so little contact there was no need to articulate Unitarianism or Universalism in a way that spoke to the black experience. The Unitarian congregations that had the most success with integration had ministers who were social activists: Jenkin Lloyd Jones at All Souls in Chicago; Holmes and Donald Harrington in New York City; Stephen Fritchman in Los Angeles; Leslie Pennington, Jack Kent, and Jack Mendelsohn at First Unitarian in Chicago; Rudi Gelsey in Philadelphia; A. Powell Davies in D.C.; Tracy Pullman in Detroit. Freedom was iconic for Unitarians, and a black, professional, socially concerned class responded, in part because it was politically progressive, in part because it freed them from some of the spiritual excesses of the black church, and in part because in the ’40s, ’50s, and early ’60s integration was avant-garde.

Universalism was different because it was difficult for African Americans to embrace. A loving God who saves all is, for most African Americans, a theological non sequitur. Why? In an article entitled “In the Shadow of Charleston,” Reggie Williams writes about a young black Christian who said, during a prayer group following the murder of nine people at Emanuel AME Church in 2015, “that if he were to also acknowledge the historical impact of race on his potential to live a safe and productive life in America, he would be forced to wrestle with the veracity of the existence of a just and loving God who has made him black in America.” This is the question of theodicy: How do we reconcile God’s goodness with the existence of evil? In the context of Charleston, the context of Jim Crow, the context of slavery, what is the meaning of black suffering? Why has such calamity been directed at African Americans? If God is just and loving there must be a reason. If there is no reason, one is led to the conclusion that God is neither just nor loving.

Hosea Ballou’s Ultra-Universalism, the “death and glory school” in which all are saved and brought into God’s embrace upon death, is mute on this. In fact, it trivializes black suffering. What is the meaning of enslavement if the master and slave are both redeemed? The way black theology answers this question is that God is the God of the oppressed; that God through Jesus, who suffered, identifies with the oppressed and will comfort and lift them up. This requires that a distinction be made between the oppressor and the oppressed. What kind of God makes such a distinction? A righteous, judging God: the God of the Old Testament. Surveys tell us this is the kind of God in which the vast majority of African Americans believe. Such a belief makes sense of their lives because it is concurrent with a nightmarish experience. What slave could look forward to an afterlife shared with the master who owned and raped her, the foreman who whipped him, or the Klansmen who lynched him? None.

I can only hypothesize that the Restorationists, rather than Ultra-Universalists, might have offered an answer of sorts. Yes, the oppressors would enter heaven. When? At the end of time, or after eons of repentance. But the only answer that would have counted would have been the lived one—the one that would have evolved if more Universalists had stood more consistently with the enslaved and disinherited and thus spoke of and to their experience. With few exceptions, they did not.

Today there are elements in Universalism that could make us, as Unitarian Universalists, as ineffectual now as in the past. The old Universalist adage “the supreme worth of every person,” or as we now say, “the inherent worth and dignity of every person,” invites some to say, “Yes, black lives matter, but all lives matter.” It is true, but when offered in response to “Black Lives Matter” it means something else.

In saying “All Lives Matter” UUs telegraph that we do not really understand. It is a variation on Universalism’s old theological pitfall. When it does not protest the systemic devaluing of black lives it obfuscates an important distinction. Saying “All Lives Matter” tells African Americans we do not know the difference between privilege and oppression. Hear how it echoes our religious ancestors. They said, “God is love” and “We are all God’s children,” but with regard to African Americans they did not act in accordance with that belief, nor did they try to articulate how it might speak to black suffering. Why? Because given their social and geographic location blacks were invisible.

African Americans, however, were visible in a particular way. White UUs saw blacks when it served their ego needs. That is to say, black lives didn’t matter—except insofar as white folks got to feel good about themselves as abolitionists and civil rights activists. Many who went to Selma—James Reeb, Orloff Miller, Clark Olsen, Jack Taylor, Fred Lipp, and Gene Reeves, for example—had close relationships with African Americans, but the majority did not.

“I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me . . .,” writes Ralph Ellison in Invisible Man. “When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination—indeed, everything and anything except me.” That has been the black experience within Unitarian Universalism.

We were invisible in leadership until following the walkout at the 1969 General Assembly; then the UUA had no choice. During the ’50s and early ’60s the pattern was to have an African American on the UUA Board of Trustees, on the Women’s Federation, on a commission. In 1967, of the thirty-two people nominated for denomination-wide elected positions, one was a member of the Urban League, two belonged to Human Relations Councils, five to the NAACP—and they were all white. Not until 1969, when eight African Americans were elected—including four to the Nominating Committee and two to the Commission on Appraisal—did that change.

On the UUA staff in 1969 there was one black person in a professional position, six secretaries, and three janitors. Since then African Americans have been widely represented in elected and appointed positions, including William G. Sinkford’s eight years as president of the UUA. In 2016 there were six people of color in managerial positions, including President Peter Morales. Because we are so embedded in institutional leadership roles there is no going back, and yet . . . and yet in 2016 four of the UUA’s five service workers (80 percent) were people of color, while forty-three of the fifty executive and first management level positions (86 percent) were held by white people. That there is no going back does not say we do not have a long way to go. (After President Morales resigned in April, the interim co-presidents announced new staff diversity goals, which aim for 40 percent people of color/indigenous people in executive, managerial, and professional roles.)

What our tortured, tragic, disappointing history teaches us is that change is incremental. It takes time. In the process many people of color have been wounded, are wounded, and will continue to be. But change is inevitable and seems to be accelerating.

Consider ministry. There were no African American UU ministers in 1929. Joseph F. Jordan had died and Ethelred Brown’s fellowship had been withdrawn. In 1955 there were four, in 1962 eight (including one Hispanic), in 1988 around twenty, in 2000 twenty-six, and today at least 112 people of color. That growth followed upon the Commission on Religion and Race’s establishment in 1965 of the Committee Toward Integrating the UU Ministry and the Black Affairs Council’s demand for support of black ministers in 1968. Around 1981 the Committee on Urban Concerns and Ministry pressed the UU Ministers Association and the Ministerial Fellowship Committee to allow ministers credentialed by other denominations to seek UU settlements, and the MFC began granting dual fellowship to African American ministers joining us from other denominations. In 1987 the Department of Ministry established an Affirmative Action Task Force. In 1989 the African American UU Ministries was founded, and in 1997 DRUUMM (Diverse and Revolutionary UU Multicultural Ministries) evolved from it. Today, religious professionals of color are supported by an annual gathering called “Finding Our Way Home.” The list it draws from includes 250 names of ministers, religious educators, musicians, administrators, and seminarians.

I estimate that the number of ministers of color is now doubling approximately every twelve years. There is a critical mass. The shift to become a more culturally inclusive faith will continue.

In the fifty years since the black revolution within Unitarian Universalism began at the Emergency Conference on the Black Rebellion in October 1967 the pace has been slow, but it has been faster than the twenty-five years following the AUA’s “Resolution on Race Relations” in 1942. In religious education it took ten years after 1967 before anything substantial appeared and twenty years before it became systematic; it took fourteen years after the rebellion before the first scholarship about the black experience in our denomination appeared, and twenty-four before the first meditation manual featuring black voices appeared.

The time in Unitarian Universalism when black lives didn’t matter has passed. Nonetheless, change is generational, incremental, and bruising. It comes, but not necessarily on our time schedule. We have fallen short and will again, and when we do we need to pause and pray and ask, “What does love demand of me?” and then stand up and try again. Impatience is not what sustains us, but rather dreams, hope, work, and companionship—the chance to pour out one’s life for the faith, principles, and people whom we value.

Adapted from Mark Morrison-Reed’s 2017 Minns Lecture, delivered March 31, 2017, at First Church in Boston. Watch the 2017 lectures, “Historical and Future Trajectories of Black Lives Matter and Unitarian Universalism,” by Morrison-Reed and the Rev. Rosemary Bray McNatt, president of Starr King School for the Ministry, at minnslectures.org. The annual lecture series, endowed by Susan Minns to honor her brother Thomas Minns, has been sponsored by First Church in Boston and the Society of King’s Chapel in Boston since 1942.