Advertisement

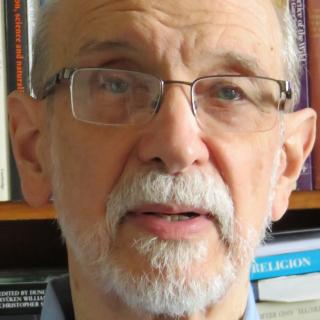

Jerome Stone still remembers the day he got the call that his father had died. He hung up the phone and slumped onto the living room sofa. His daughter, eight years old at the time, asked what was wrong. “Oh, Dad!” she cried, and threw her arms around him.

Stone, a Unitarian Universalist theologian, sometimes tells the story of his daughter’s hug to illustrate his theology. Her hug, he explains, was an unexpected and freely given gift of comfort and love—what religious people call grace. For him, this gift was not the work of a personal God nor was it a “mere” event. He understands his daughter’s hug as transcendent grace because it came from outside of the situation in which he found himself.

Though technical language and dry prose often mask the personal questions and concerns that drive their work, theologians are inspired by the business of daily living. Stone is no exception. One of his worries is that Western secularization has undermined our ability to appreciate the sacredness of life’s many blessings. As a result, we are closed off from important resources of grace, which offer us renewal, meaning, and healing.

While Stone wishes us to grow more attentive to life’s transcendent, sacred goodness, he resists the urge to say more about the origin of that goodness. In his view, such explanations are excessive because they can’t be defended.

Stone calls his “this-worldly” theology a minimalist vision of transcendence, hence the title of his best-known book, The Minimalist Vision of Transcendence: A Naturalist Philosophy of Religion.

Stone prefers the term “the transcendent” to the word “God.” But this wasn’t always the case. The son of a Congregationalist minister, he grew up with God-talk. His father understood the Bible as symbolic, poetic, and infused with prescientific understanding, and so, for him, it did not conflict with science. Stone fondly remembers car rides to Sunday evening services when he and his father would discuss the differences between atheism, deism, and theism. They sometimes chatted about Ralph Waldo Emerson’s views on the over-soul and on the importance of self-reliance even in times of despair.

While in high school, Stone attended a church youth program, including church camp. The general tone, he recalls, was one of attentiveness to doing good and of responsibility to the world: “Instead of oppressive moralism, there was offered a vision of service.”

But as a 16-year-old freshman at the University of Chicago, he had a conversion experience. Until then, his religious life had mostly focused on striving to be morally good and on seeking God’s forgiveness when he failed. But two Easter services that year, one at Chicago’s Methodist Temple, and the other at the University of Chicago’s Rockefeller Chapel, led him to begin reflecting deeply on his closely held beliefs. Stone eventually concluded that his and other people’s “ultimate significance” did not depend merely on their actions.

Stone loved many of Emerson’s ideas, but he decided that Emerson had gone too far in his insistence on self-reliance. Stone continued to see the necessity of working through despair, moral or otherwise. Still, he now realized that humans could not always travel this road alone. Nor should we want to do so. No doubt, striving to be and to do good mattered and should be taken seriously. But unexpected and uncontrolled gifts of help and comfort offered by others and by the world mattered, too. A balance between self-reliance and other-reliance was not just possible—it was desirable. There was value in being open to transcendent grace, and in receiving it.

By the time he completed his master’s degree, Stone was a Congregationalist minister married to his college sweetheart, Susan, and was the father of two children. While serving a congregation to support his family, he pursued a Ph.D. in theology at the University of Chicago. As he began to write his dissertation, Stone realized that his theology had shifted toward a thoroughgoing “there-is-nothing-beyond-this-world” naturalism. He had lost his faith in a personal God. What to do? His adviser helpfully noted that all of the world’s religions point to something beyond the self. He recommended that Stone focus on theologians who appeal to secular or horizontal (instead of vertical) experiences of transcendence.

Thanks to this suggestion, Stone completed his doctorate and became a college professor. He officially became a UU after he retired from teaching at Harper’s College, although his theology had long had a deep resonance with Unitarian Universalism. As his theology developed, Stone never lost sight of his discovery of the importance of grace. However, he also never lost sight of his pre-conversion views about the value of judgment. Judgment offers the possibility of criticism and challenge. The contemporary world’s loss of resources of judgment is the other concern at the core of Stone’s work. He worries that Western secularization (in his words, “self-assured secularity”) has led to the loss of any perspective from which to call into question our society’s “attachment to relative meanings,” and our own.

Just as Stone calls for the recovery of transcendent resources of grace, he calls for the recovery of transcendent resources of judgment.

Stone tells another story from his life to illustrate how transcendent resources of judgment fit into his theology. During the late 1960s, it was still legal in Evanston, Illinois, the city where he lived, for property owners to refuse to sell or rent housing to Jews and black people. To pressure the city council into passing an open-housing ordinance, the black community, together with the liberal white community, organized weekly marches. Pulled by a moral demand to act against Evanston’s discriminatory housing practices—a demand coming from outside of his everyday routine—Stone responded. Though he was a graduate student, teaching full time and raising a family, he juggled his schedule so that he, too, could march.

For Stone, the insistent call to overturn immoral laws inspired him to join the protesters. His daughter’s unexpected hug was a gracious gift of renewal. Both the challenge and the gift came from outside of the situations in which he found himself. Transcendent resources of judgment and of grace work in tandem, Stone believes, to deepen the human spirit.