Advertisement

With most commuters driving east out of the city, toward Dallas or one of the metroplex’s myriad suburbs, the rush-hour drive west into downtown Fort Worth felt too fast. The surprisingly short trip heightened our anxiety.

I drove the rental car up Belknap Street and parked. The sun bore down on us, a pristine late March day in Texas. Despite the afternoon’s warmth, we shivered as we stared at the imposing building: the Fort Worth police station. Raziq glanced down at his clothing as if to question his attire: a black shirt and naturally faded blue jeans, with the black sneakers he’s rarely without.

“Internal Affairs is actually in the same building as the city jail. That’s …” He apparently didn’t have the words. Bewildered, Raziq shook his head, his trademark short dreadlocks twisting from side to side.

As we walked into the station, we didn’t feel like Raziq Brown and Kenny Wiley, the duo of promising, young Unitarian Universalist leaders of color. My khaki shorts and shirt from a UU youth camp suddenly felt like a futile grasp at respectability. Here we were our given seldom-used names: George Brown and Kenneth Wiley, twenty-something black men walking into the building that served, among other things, as the Fort Worth city jail.

A middle-aged white woman stopped me just inside the main door: “You put your parking sticker in the wrong place.” She pointed to my car and smiled, her understated drawl reminding me of white neighbors from my suburban Houston childhood. “Don’t want you to get a ticket, now.” Worried about leaving him, I glanced at Raziq, who nodded before checking in at the front desk. As I walked away, I heard the desk officer ask him, in a voice apparently meant to be welcoming, “Weren’t you and your cousin here last week?”

We were not. That we looked like two previous visitors to the station, though, struck eerily close to the reason Raziq held a six-page letter in his hands, and to why I’d flown from Denver with only three days’ notice. Racial profiling—something easy to spot and difficult to prove, like many examples of systemic racism—had caught Raziq napping, metaphorically and literally, just seven days before.

The East Fort Worth Montessori Academy sits on a hill that can’t seem to decide whether it belongs to the wide-open spaces of west Texas or to east Texas’s wooded greenery. Much of Fort Worth feels that way: distinctly western, with Deep South influence. A stunning sunset casts its shadow over town even as trees block just enough of the view to prevent the scene from fully feeling like one from Friday Night Lights.

Raziq’s mother Joyce—seemingly known by all of East Fort Worth, and ubiquitously referred to as “Ms. Brown”—runs the school. To help Ms. Brown out and make ends meet, 25-year-old Raziq has worked as a custodian while finishing his undergraduate degree. The school serves over 200 elementary-aged children, mostly black and Latino/a students from the east side. During the day, children laugh, ask thoughtful questions, and prepare for the upcoming musical.

It is Tuesday, March 24, and Raziq is tired. He heads to work wishing he’d napped first. Raziq’s coworker Richard, a reserved Sudanese man with a captivating smile, lets him know that he’d accidently set off an alarm earlier. “Don’t worry about it—I shut it off and talked to the security company,” Richard assures Raziq.

Night brings Raziq quiet, and a migraine. Wanting to fend off the headache, Raziq finds a classroom—Room 10—and, partway through his shift, lies down for a short nap.

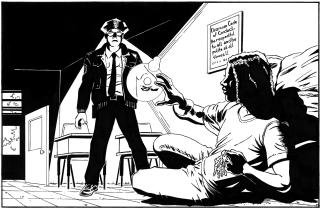

A stack of yellow pillows rests in the corner nearest to Room 10’s main door. Above them, a poster outlines the classroom Code of Conduct, which says, among other things, “Be respectful to all, and be polite at all times.” Across the classroom is a screen door that opens onto a private playground—that someone left unlocked earlier in the day. A few minutes into Raziq’s nap, a sharp knock at that door, and a bright flashlight, stir him.

A white police officer tells Raziq to get up and leave the building. Standing and wiping his face, Raziq tells him that he works at the school. He attempts to show his school ID and key to the building. The officer ignores both—Raziq’s biggest indication that the stakes of his every movement are dangerously high. In his letter to the police and other officials, Raziq, who’d opened his phone to call his mother, describes what happened next:

The officer told me to “put the phone down before I have to put my hands on you.”

I closed the menu on the phone and put my hands above my head, saying, “Sir, please don’t put your hands on me. I will comply.”

He replied, “You know what?”

He grabbed my wrist, twisted it around my back, slapped cuffs on me, and told me I was “resisting arrest.”

When I asked him what I was being arrested for, he simply said, “resisting.”

As he marched me through the dark playground at the school I saw that the white officer’s black partner had found my coworker, Richard. He was not handcuffed.

I yelled out to Richard, “Call my mom and tell her the police are arresting me.”

He did so, but not until after the black officer harassed my coworker, pressuring him to remain silent and indicating that he should not inform the CEO that her son was being arrested for trespassing in his place of work.

Over the next few minutes, they accuse Raziq of robbery, of squatting in the building, and, again, of resisting arrest. The officers do not believe that his mom runs the school. They won’t believe his sister is the school’s principal. They ignore his insistence that he belongs there.

When they ask why he was sleeping, Raziq tells the officers, “I had a headache. I had just put my head down for a minute. I work nights, man …”

The black officer cuts him off. “I work nights too, [and] I don’t take naps.”

The white officer turns to Richard and asks, “Does he let you do all the work while he just sleeps and gets paid?”

“Am I being arrested for taking a nap?” Raziq asks.

Minutes later, Ms. Brown arrives, incensed; the officers quickly remove the handcuffs. Raziq’s wallet and phone are still in his hands.

“I told them the truth. I tried my best to verify my identity, and had a coworker present to verify who I was. But when I tried to get the police in touch with the responsible parties, they physically kept me from doing so,” Raziq told me later.

“Young black women and men are shot by cops for ‘resisting arrest’ all the time,” he wrote on Facebook. “I can’t fully express how scary it is when a man with a gun tells you ‘you’re fighting and trying to walk away from me’ as you stand still, attempting to comply.

“I almost got arrested for taking a break at work while black—and that is not okay.”

“Where did these stats come from?”

An officer from the Fort Worth Police Department’s Internal Affairs office—a young, fit, white male officer—had just finished reading Raziq’s detailed letter of complaint.

Raziq’s voice, infused with resolve, fear, and exasperation, trembled slightly as he responded, “A friend got them for me.” He dug out his phone to look for the source.

“The signal in here isn’t very good,” the officer warned, with a slight smile.

The seconds stretched on. Raziq struggled to log on and find where the statistics in question, numbers detailing racial profiling by Fort Worth police, had come from.

The Internal Affairs officer was far from the first person to read Raziq’s letter. An avid social media user, Raziq posted a version of the letter on Facebook the day after his detention. He’d concluded it with, “I don’t post this because I feel victimized in any way … This is not the first time I have been accosted by police. I post this because Facebook is a place where you post about the everyday.”

Myriad friends and acquaintances shared the letter, accompanied by reactions nearly universal in their shock and horror. Many—especially white friends and fellow Unitarian Universalists—were quick to praise Raziq for his “calm, measured” reaction. On our drive to the station, Raziq had brought up those responses, which were intended to praise his tactics but had the impact of suppressing his emotions. “I was calm in the moment because I had to be, but even afterwards, it felt like I wasn’t supposed to be sad or angry,” he told me. “Like I had to just sit there and politely disagree with what happened to me.”

For months, Raziq and I had been talking intensely about the state violence facing unarmed black people across the country. Anger and fear permeated our conversations. Now I realized that, in this moment, Raziq badly needed to feel his own humanity—to feel his own tears, his own rage, his own disbelieving laughter, with others who could truly understand.

As Raziq scrolled through his phone and the officer shifted his weight slightly, it occurred to me that our parents, living and deceased, might have foreseen his need. The scene—Raziq sitting in the police station looking up statistics about racial profiling, minutes after a desk officer had assumed we’d been there the previous week—was indeed absurd.

Finally the officer said, “I think I know where [the stats] came from. I’m going to check some things out. Can you wait fifteen minutes?”

Raziq nodded as his shoulders relaxed. He glanced at me. “Thanks for being here, man.” I shook my head sadly and said, “Don’t thank me. Thank our parents.” I wished they were here.

Dr. James T. Brown and Ida Stewart, my mother, were good friends in the 1990s. They had an easy rapport. Black Unitarian Universalist leaders in Texas, completely comfortable in large groups of white people, each valued black community. Ms. Brown did, too. As Raziq and I became teenagers, their gentle insistence that we become friends transformed into a full-court press. Raziq and I resisted for most of high school. Though we did not know it until later, our parents, especially our mothers, were singing from the same hymnal.

“This world, beautiful though it can be, is absurd, and you’ll need each other one day,” my mom liked to say. “Become friends with that boy,” Ms. Brown would tell Raziq. Dr. Brown would smile and nod.

Maya Angelou turned forty on April 4, 1968. She had planned a big party in Harlem, with many of the day’s black intellectual elite among the guests. History had other ideas; Dr. King’s assassination sent Angelou into a weeks-long depression. It was fellow writer James Baldwin who helped her dig out of it. Angelou recalls Baldwin’s assistance in her book A Song Flung Up to Heaven, where she writes that laughter and ancestral guidance got her through:

There was very little serious conversation. The times were so solemn and the daily news so somber that we snatched mirth from unlikely places and gave servings of it to one another with both hands… .

I told Jimmy I was so glad to laugh.

Jimmy said, “We survived slavery… . You know how we survived? We put surviving into our poems and into our songs. We put it into our folk tales. We danced surviving in Congo Square in New Orleans and put it in our pots when we cooked pinto beans… . [W]e knew, if we wanted to survive, we had better lift our own spirits. So we laughed whenever we got the chance.”

It took Raziq a few days to realize just how shaken and upset he was, and it didn’t immediately register with me that I ought to go and visit him. Aloud and internally he searched for alternative explanations for what happened to him, something other than racial profiling. For some black folks, especially well-off millennials, the internal dance of navigating race brings exhaustion because so many of us were convinced by white friends growing up that racism no longer mattered, if it even existed. Maybe that had nothing to do with race. Maybe that cop is rude to everyone. Maybe I’m just reading too much into it. Maybe I shouldn’t complain. We can talk ourselves into circles of anxiety and confusion.

Raziq attended a UU antiracism forum the day following the harrowing encounter. He had the room of white UUs laughing; two of our mutual friends, when I texted them, said he “seemed fine.” He worked to convince his friends and online community that he was okay, that it was just life.

But it shouldn’t be just life. The healing kind of laughter doesn’t minimize the seriousness of what happened or give up the struggle against injustice. The healing kind of laughter comes from being in community with people who truly understand. Raziq’s parents, and my mother, wanted to prepare us for the absurd. They wanted us to understand that life makes little sense sometimes, and we’d need black community to get through it. Sitting there in Internal Affairs, we understood at last. Sometimes you need someone who just gets it. Someone willing to go with you into a police station to complain about the police, as though there’s any hope that they’ll do something about it. Our parents understood that, as black folks, we would need each other.

Two days after the officers accosted him, Raziq called me again. “I’m not okay,” he said, his voice breaking slightly, as I paced the aisles of a Target in southeast Denver.

“Yeah, no kidding.” I paused for a moment. “Man. I can come visit, if you like.”

The man at Internal Affairs returned and told us that the officer’s camera had not been turned on until Raziq’s mother had shown up, so there was no way to prove—or disprove—what Raziq was claiming about his treatment. “You weren’t arrested. You were detained,” the officer told him. “Since there was a burglary call, they had probable cause to handcuff you. There’s a rudeness complaint to be filed here, and I don’t know why the officer did that to you.” Then, he added, “Nights can be tough.”

Raziq nodded. He looked disgusted, defeated, and relieved. It was over, more or less. “We’ll be in touch with you,” the officer said, not unkindly. (Raziq has heard nothing more.)

Raziq glanced up before saying, “Nights really can be tough.” He would know.

The officer shook Raziq’s hand, then mine. “Have a great day.”

Stunned and exhausted, we chose to stick with our plan of going to the downtown YMCA, a tradition of ours. As usual we’d split up for awhile—I’d play basketball while he jumped rope and ran, and then we’d lift and do abs together.

Still dazed as I warmed up my jump shot, I realized a white guy about my age was trying to get my attention. “Wanna get a game goin’?” he asked. He wore a purple TCU Football shirt and white Baylor shorts, a combination I didn’t know the state of Texas allowed. He asked if I’d get a team together from the other folks milling around. The first person I asked was a 5’9”-ish black woman with shoulder-length braids who looked about 30. She seemed taken aback.

“Sorry,” I said, not really sure what I was apologizing for.

“No, no, I’ll play—it’s just … guys don’t usually ask if I want to run.” She smiled slightly as I sighed in understanding. “Well, I’m hoping you do,” I said, and we shook hands.

We got three more teammates, two middle-aged white guys and a 5’10” black teenage boy, and the game began.

That men rarely invited her into pickup games would have been ridiculous and troubling if she’d had no game at all. As it was, she could flat out play basketball. Her first two shots didn’t even think about hitting the rim as they swished in from long range. Once the men on the other team realized how good she was, they quickly—and predictably—overcompensated to try and stop her, leaving the rest of us open.

Tamara—not her real name—dribbled into the paint off a screen I set for her in the high post. As two guys jumped to block her, Tamara fired off a no-look bounce pass right to my hands. I contained my glee long enough to convert the layup. Everyone watching went wild. As we jogged back down court to play defense, we made eye contact, and she winked and smiled wryly. It would be a bit before I connected that wink to Raziq’s experience.

Tamara winked, I think, because she sensed I understood how absurd it was that guys rarely asked her to play. We won three games together before Raziq came up, ready for our lifting session; in each game, Tamara was the best player on the floor. The prejudice she faced, on the court and, likely, elsewhere, was ridiculous. That wink was her way of finding a way to laugh about an injustice that hurt. As I left the court, we bumped fists and nodded.

“That was great—I needed that,” she said. I did, too.

After our workout, Raziq and I drove east on I-30 toward his house, the car ride quiet except for one of the local hip-hop stations, K104 FM, playing in the background. Almost simultaneously, we realized what song was playing—Houston rapper Chamillionaire’s 2006 smash, the anti-racial profiling hit “Ridin’ (Dirty).” We looked at each other in disbelief. He reached for the volume and turned it up:

They see me rollin’, they hatin’,

Patrolling, they tryin’ to catch me ridin’ dirty

Tryin’ to catch me ridin’ dirty

The racial profiling statistics Raziq had used, by the way, had come from the Fort Worth police themselves, in a report from a few years earlier.

In no time the two of us had the song blasting in my car as we rapped along.

Cause they denyin’ that it’s racial profiling

Houston, Texas: you can check my tags

Mid verse, Raziq and I looked at each other and did the only thing that made any sense—something our mothers, and maybe even James Baldwin and Maya Angelou, had likely seen coming.

We laughed.

Raziq now strives to get his custodial work done much earlier in the evening. He and Richard are careful not to set off alarms. The approaching Texas summer means longer days, which helps.

On this day, it is sunset again. During a walk through the school premises together, Raziq stops outside the door the white police officer had entered. He slowly drags his left foot on the gravel. The sound activates a memory of mine—ours, really—buried deep within: Raziq and me as children, walking impatiently behind his father and my mother at UU summer camp in Oklahoma as they chatted away and laughed uproariously as we headed down to the lake.

As a kid I didn’t understand why they laughed so often. Dr. Brown passed away in 2012, and my mom died of cancer in 2011, so no longer can we ask them. I suspect, though, that they hung out and laughed together for the same reason my mom laughed so much with her sisters, with her best friends, and with other black women in suburban Houston—and for the same reason they insisted that Raziq and I become close. They laughed not to avoid the racial realities of this country, but to maintain the strength to endure and resist them. They laughed in order to survive.