Advertisement

The year Chuck Collins turned 16, his father took him aside for a man-to-man talk. Edward Collins told his son that he had set up a substantial trust fund for him.

Chuck remembers feeling utter amazement. The great-grandson of Oscar Mayer and an heir to the wiener fortune, he had grown up living comfortably, but not lavishly, in suburban Detroit. Now, as his father spelled out, he realized he would not have to work for money unless he wanted to. His dad also stressed his hope that the money would not change his son or his life goals.

It didn’t. However, events took a very different course from the one the elder Collins had so carefully planned. Ten years later, in 1985, Chuck Collins gave away every penny of his inheritance, nearly half a million dollars, to foundations and groups that he knew needed funding—organizations working for the environment, peace, racial equality, and indigenous and gay people’s rights.

“Wealth that just creates more wealth seemed wrong,” says Collins, whose book in support of preserving the estate tax, Wealth and Our Commonwealth: Why America Should Tax Accumulated Fortunes, written with William H. Gates Sr., has just been published by Beacon Press. “At age 26, with no family responsibilities, I didn’t want it. I didn’t really need it. I wanted to make my own way. And I knew other things needed it more.”

Before cashing in the fund, Collins wrote a letter to his father, a libertarian conservative, explaining his plans. A concerned Edward Collins flew to meet him the next day. In their second man-to-man talk about the money, the elder Collins wanted to make sure Chuck was considering how he would support any children he might have: “What if you have a child who has Down syndrome? Think about the cost of the care,” Chuck remembers his father asking.

His father also asked if he considered himself a Marxist who had to renounce his class background. Chuck, a lifelong Unitarian Universalist, tried to reassure his dad, saying that he would feel comfortable with the label Gandhian or Christian, but he was not a Marxist.

After two days together, Chuck remained unswayed. “The decision to give away my wealth felt like the first real decision I’d ever made,” he wrote in We Gave Away a Fortune. “Life presents only a few crystal-clear opportunities to take risks for what you believe, and this was one.”

His father needn’t have worried. Coming into his inheritance changed Chuck Collins not at all.

Now 43, a father himself, and a cofounder of United for a Fair Economy (UFE) in Boston, a nonprofit organization widely praised for its creative ways of illuminating the growing wealth gap, Collins has always been a social activist. As a first grader, he raised $125 for guide dogs for the blind by organizing a backyard fair for his class. In fifth grade, he wrote and circulated in his neighborhood an environmental leaflet that began, “Don’t throw this paper away—it will cause pollution.”

After college, he worked for the Institute for Community Economics in Springfield, Massachusetts, which was building a nationwide movement of land trusts, cooperatives, loan funds, and credit unions in poor communities. As he traveled to places like Appalachia and Maine, where most land is owned by absentee corporations, he formed a critique of a system that kept rich people rich and poor people poor. He began to see that inherited wealth—including his own trust fund—was a piece of the problem he was working to solve.

“Giving away the money was a necessary step for me to move along in the work I do,” he says. “Two decades later, I’m doing this work because that was part of my journey. It gave me insight into the way concentrations of wealth undermine equality and democracy.”

Collins has been coauthor of three previous books about economic inequality: Robin Hood Was Right: A Guide to Giving Your Money for Social Change (2000), Economic Apartheid in America (2000), and Shifting Fortunes (1999). But when he finished the new manuscript defending the estate tax, he knew he wanted his father to read it.

“Because of my relationship with my dad,” he says, “I know how thoughtful conservatives think, and I respect them. I knew my dad supported the repeal of the estate tax, and I knew he would find the holes and weaknesses.”

Edward Collins did a line-by-line edit that, for both men, recalled the way he used to go over his son’s term papers, flagging “Syntax!” and other corrections in the margins. This time, though, at the end of the text, he wrote large: “You changed my mind.”

For Chuck, it was the best review he’d ever gotten.

“My former view had been that the estate tax was a confiscatory tax that should be done away with,” the elder Collins says. “But Chuck’s book definitely brought me right on board. My realization that came from the book is that the estate tax is critical to maintaining our democratic society.”

In December 2000, Chuck Collins got an e-mail from Bill Gates Sr. Collins works with plenty of rich and famous people through a UFE project called Responsible Wealth, which signs on people in the top 5 percent of wealth to work toward economic equality. Names like Paul Newman, Annie Dillard, Ben Cohen, Ted Turner, George Soros, various Rockefellers, Roosevelts, and other successful artists, executives, and heirs are apt to show up in Collins’s in box.

But this e-mail out of the blue seemed a bit suspicious. He suspected a prankster at the UFE office—where a good sense of humor is a job requirement—was joshing him. As the story has evolved through many public retellings, Collins fired back: “Yeah, and I’m Minnie Mouse.” Turns out, it really was Bill Gates’s dad, who is a founding partner of a Seattle business-law firm and now director of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which funds projects to improve health in the developing world. And he couldn’t have been more serious.

Like Collins, Gates considered the estate tax a moral issue and was deeply disturbed by the movement to repeal the tax—which President George W. Bush had made a top domestic priority when he took office. Especially troubling to both men was that, while repeal of the tax was not popular in polls, no one was arguing why it should be preserved. “We are now living in a second Gilded Age,” Collins says. “There is as great a disparity of wealth now as there was then. And we’re about to eliminate the estate tax? It’s totally the wrong way. It’s the one check we have.”

Once Gates got Collins on the phone, he asked, “What can we do?”

Collins, the organizer, didn’t skip a beat: “Draft a public statement, get media coverage, testify before Congress, write letters, op-ed pieces.”

Gates replied, “I’m game. Let’s do it all.”

From both coasts, they got to work. First on the agenda was the kind of event Collins has become known for: creating a news story that steals the limelight from the mainstream newsmakers, with a sound bite too good for editors to resist: Tax Our Estates, Wealthy Say—It’s Only Fair.

On Valentine’s Day 2001, UFE’s Responsible Wealth released its Call to Preserve the Estate Tax, a petition that has been signed by more than 1,000 of the wealthiest people in the country and is still taking signatures. Newsweek called it the “billionaire backlash.”

Unfortunately, most members of Congress had already pledged their votes. In June 2001, President Bush signed a bizarre compromise bill crafted to comply with congressional budget mandates.

As the law stands, the estate-tax percentage will be gradually reduced over the next ten years. Complete repeal will occur in one year only — 2010. After that, the 2001 estate-tax rate will go back into effect. The tax’s opponents have continued to introduce bills to make the repeal permanent, but none have passed.

Stimulating a lively debate over the estate tax is no easy task, Collins is the first to admit. Most people will never pay it nor receive any perceptible benefit from its repeal. Currently, the first $2 million of a couple’s estate is exempt, so only the wealthiest 1.5 percent of the population will pay any estate tax.

Even more significantly, in the two years since the temporary repeal was passed, terrorism and threats of war have eclipsed coverage of the estate tax issue. Yet the repeal stands, and efforts to make it permanent continue. Permanent repeal, Collins argues, would threaten the very fabric of our democracy and of a society that holds equal opportunity as its ideal.

Contrary to what its opponents argue, the estate tax is a fundamentally American institution, Collins and Gates assert in Wealth and Our Commonwealth. Revolutionary era patriots—Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, Noah Webster, Samuel Adams, James Madison—rejected anything that smacked of the stratified aristocracies of Europe. Visiting Europe, Jefferson and Adams wrote of being appalled by concentrations of vast wealth passed down for centuries. Absolutely central to the success of the new republic, they argued, was fair, broad, and equitable distribution of wealth and property.

President Theodore Roosevelt first proposed the current estate tax in 1904 in response to the corruption and excesses of the Gilded Age. Progressive Era reformers feared that if wealth concentration continued unchecked, most of the U.S. population would end up subjects of the robber barons, as Europeans were to their aristocracies. The tax was signed into law in 1916.

Today’s estate-tax opponents have portrayed it as an affront to individualism and personal initiative. A big myth put forth in support of repeal, Collins says, is the notion that “I made this money myself, so I don’t owe anything.”

“But there’s a whole other piece of the story,” Collins says. “Let’s do an accounting here. What about how other people’s efforts—employees, teachers, parents—and a stable government and economy, privilege, God’s grace, and luck all helped you?”

In the book, Collins and Gates propose this scenario: Imagine that God is sitting in his (or her) office. He summons the next two beings to be born. One will be born in the United States, and the other in a poor country in the Southern Hemisphere. God’s treasury has suffered some losses in technology stocks, so he has come up with a scheme to auction off the privilege of being born in the United States, where he knows there’s a wonderful infrastructure of public health, education, and market mechanisms that enhance opportunity. Each spirit is to write down the percentage of its net worth that it is willing to pledge to God’s treasury on the day it dies.

“What is it worth to operate within this marvelous system?” Collins and Gates write. “What’s wrong with people who accumulate $20 million or $100 million or $500 million putting a third of that back into the place that made possible the enormous accumulation of wealth for them? What is it worth to be an American?”

So why aren’t the huge gaps in income and wealth more of an issue in America? That was the question that Chuck Collins and some of his fellow organizers at the Tax Equity Alliance of Massachusetts were puzzling over back in the early 1990s.

The question was at the root of so many trends they were seeing then—and still see. Real wages are falling for many working people, as UFE points out. Funding for public education is declining, eroding its quality. Higher education, health care, and decent housing are being priced out of reach of working people. The United States has more illiteracy, more and deeper poverty, more violent crime, larger prison and homeless populations, higher infant mortality, and lower life expectancy than any other advanced nation. Meanwhile, a tiny, fabulously rich minority is amassing huge fortunes at an accelerating rate. Why aren’t people talking about it?

Economics has been called the dismal science—dismally boring, that is. Collins, who has a master’s degree in community economic development, has taken that as a personal challenge. If there is to be any debate or change, he figures, ordinary people have to understand the wealth gap and what is wrong with it, just as the early patriots and Progressive Era reformers did.

In 1995 Collins and Felice Yeskel, now director of the Stonewall Center for gay and lesbian students at the University of Massachusetts, put together a nuts-and-bolts workshop called The Growing Divide, combining user-friendly economic charts and concrete suggestions on how to take action. That workshop has taken on a life of its own. Hundreds of people in religious groups, unions, and on campuses have been trained as workshop leaders, and tens of thousands have taken it and still do.

Building on the success of The Growing Divide, Collins, Yeskel, and Boston College sociology professor Mike Miller got seed money from the Little Sisters of the Assumption to cofound United for a Fair Economy. From the beginning, UFE has had close kinship with religious groups working on economic and social justice.

“UFE does the best work in the country on the gap between rich and poor, which is, for many of us in the religious community, a fundamentally moral and biblical issue,” says Jim Wallis, the leader of Call to Renewal, a nationwide federation of faith-based organizations working to overcome poverty.

Collins became UFE’s first employee, initially as a part-time second job. UFE now has eighteen employees and runs campaigns across the nation. Two years ago Collins hired an executive director to free him to do what he loves most — programs that inspire people and make them laugh.

“Our forte is street theater-it’s the most accessible, funny, engaging way we’ve found to connect with people,” he says. “It’s so spiritually uplifting and fun to get a message across with humor, rather than grimness. And it cracks open minds.”

When another attempt at permanent estate-tax repeal came up for a vote in Congress last summer, Collins and ten other UFE activists posed as Millionaires for Unlimited Inheritance. Dressed in top hats and tuxes or fur stoles and gowns, they took a stretch limousine to U.S. Senator Susan Collins’s office in Bangor, Maine, to “celebrate her courageous step” supporting the bill. “We called out, ‘She really understands us. We love Susan Collins.’ It was very embarrassing for her,” says Chuck Collins, who is not related to the senator. “Only twenty-four people in Maine each year would benefit from the tax cut. It’s so out of synch with Maine sensibilities.” This spring UFE “millionaires” are continuing to stage actions in a handful of swing districts on estate-tax repeal across the country.

Collins’s favorite kind of theater action is what he calls media hijacking. In 1998, Collins noticed a Wall Street Journal item announcing that U.S. Representatives Dick Armey and Billy Tauzin were planning to dump a copy of the multivolume federal tax code off the Boston Tea Party Ship as an April 15 publicity stunt.

So two UFE activists with a baby doll rowed alongside the ship in a small plastic “Working Family Life Raft,” yelling, “Don’t throw it. You’ll drown us.” Other UFE staffers had gotten aboard the ship and were chanting, “Sink ‘em with the flat tax. Drown ‘em with the sales tax.” Collins was passing out press releases on a nearby bridge. With their media advisers running amok, the flustered congressmen heaved the trunk of papers overboard—and the lifeboat capsized. The event got plenty of publicity all right, but not the kind the congressmen had planned. “All it took,” Collins says, “was a $7 raft, good timing, discipline, and creativity.”

United for a Fair Economy urges individuals and groups to create their own actions and has published The Activist Cookbook, loaded with “recipes” and encouragement for the timid. “Art isn’t something that rich people do with their leisure time-it’s something working people do with their lives,” the cookbook exhorts.

One tactic UFE recommends is to introduce stockholder initiatives, which anyone who owns $1,000 of stock in a company can do. Collins holds a small amount of General Electric stock, and every year he introduces an initiative to reduce the top five executives’ pay. The first time Collins went to GE’s stockholder meeting, he happened to follow a nun demanding that GE clean up its toxic waste in the Hudson River. Angered, Jack Welch, who recently retired as one of the ten highest-paid CEOs in the country, sarcastically asked where she wanted him to put it—in Yankee Stadium?

When his turn came, the quick-witted Collins began, “As a Red Sox fan, I kind of like the idea of putting toxic sludge in Yankee Stadium.” That got everyone laughing. Then he held up a dinky replica of another national icon to drive his own point home: “If the Washington Monument was the average CEO’s pay, then this 21-inch replica would be the average worker’s pay. But at GE, this Life Saver would be the average worker’s pay.” Again, everyone laughed at the absurdity, then listened as he explained how large disparities between executives’ and workers’ pay undermine the health of “our company” and the beneficial spirit of team building.

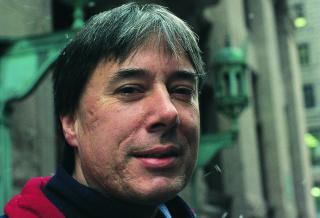

As an executive in his own organization, Chuck Collins rides his bike or takes the subway to work from his half of a two-family house in Boston’s Jamaica Plain neighborhood, which draws young political activists and immigrants alike. With lightly salted dark hair, he dresses for the office in comfortable cotton shirts and denim and carries a reusable coffee mug. His six-year-old daughter attends Boston public schools.

His wife, the Rev. Patricia Brennan, now serves as assistant minister of the King’s Chapel in Boston. The son of early members of the Emerson Church Unitarian Universalist in Troy, Michigan, Collins teaches church school and started the social-justice committee at the First Church Unitarian Universalist in Jamaica Plain, and is a trainer for workshops sponsored by Unitarian Universalists for a Just Economic Community. At the 2001 General Assembly in Cleveland, Collins introduced the resolution that resulted in economic globalization being chosen as the denomination’s Study/Action Issue—and was taken by surprise at the floor fight he had to lead to win approval.

Collins moves easily among people of all classes—from his close friendship with an immigrant single parent; to his parents and their friends; to the members of Responsible Wealth; to the intense, smart political activists he works with and trains; to high-level politicians and power brokers across the country. On the sidewalk outside his downtown office he greets the first black woman Episcopal bishop and a doctor who has been treating the homeless on Boston Common for decades.

“Chuck is a phenomenon, a lovely, decent human being,” says UFE cofounder Mike Miller. “He has a rare combination of amiability and talent, which you don’t often find, unfortunately. It’s a magnetic quality, so soft spoken and quiet, that attracts people. I consider him a real treasure.”

Over time, Collins has become increasingly closer to his father. Both say their relationship now focuses on their many similarities, especially their get-mad-and-do-something-about-it view of the world. And both relish a good political argument, which often forces them outside to spare other family members. “His influence on me has been as significant as perhaps mine on him,” Edward Collins says. “I’m quite proud of Chuck. He has changed many views within our family.”

Collins rarely thinks about the fact that he gave away his birthright. Many of his friends and colleagues don’t even know about it. When interviewed for this article, Bill Gates Sr. said he knew Collins came from money but had no idea that he’d given it away. “I’m sorry I don’t have a comparable story to tell,” Gates adds.

If Collins had to pick the label that best describes himself today, it wouldn’t be Gandhian, Christian, or Marxist, but rather “radical meritocratist,” a term coined by Andrew Carnegie in his book The Gospel of Wealth. The term describes someone who believes that each generation should “have to start anew with equal opportunities . . . [that would] bring the best and the brightest to the top.”

Yet, for those who might follow Collins’s example, there remains this stumbling block, the same one his father raised two decades ago: What if his children or grandchildren or great-grandchildren had a costly need? What if he needed expensive care in the future? Wouldn’t it be hard to justify burdening his own heirs when he was the one who gave the money away?

“I still think about these kinds of questions all the time,” he admits. “My yardstick has always been: Am I going to have special privilege in relation to this problem? Those choices continue—do we set up a college fund, or do we work to build a society where it is not an overwhelming privilege to have a college education, and you don’t have to be in debt for the next twenty years. Every day I make at least five little choices—do I take the subway or car? Do I go to the library or bookstore? Do I send my daughter to public or private school? Do you build a wall of money around your life to protect yourself, or do you invest in the commonweal? You can’t be too rigid or ideological. So you put money in a college fund and give to the United Students Association so they can work toward making tuitions lower.

“I want to cast my lot with everyone else I know,” Collins avows. “I would rather work for a society where people take care of each other and not one based on whether you can amass a small fortune to provide basic care. I’m working toward a time when the idea that I can drive as big a car as I want, use up as many resources as I want, just think about my kid and nobody else, will be unimaginable. I believe you shouldn’t have to be rich to have a decent life in this society.”