Advertisement

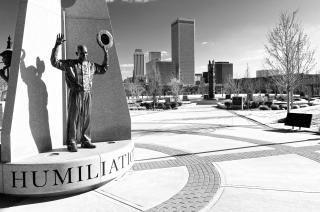

Bronze sculptures on a round granite platform mark the entrance to John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park in Tulsa, Oklahoma. One depicts a black man, his hands raised in surrender. Next to him is a white man with a rifle in each hand; a cigarette dangles from his mouth. The black man looks both fearful and resigned to his fate, hat in his left hand. The white man’s face holds a look more chilling than rage: purpose. Under each figure is a single word, in large bronze capital letters: HUMILATION and HOSTILITY, respectively.

The two words, and the sculptures above them, represent a ninety-five-year-old horror, the Tulsa race riot of 1921.

During a sixteen-hour rampage, a white mob gunned down or burned to death as many as 300 black people: an elderly couple, shot in the back of their heads as they knelt praying; one of the most prominent black surgeons in the country, shot with his hands up; more than thirty-six square blocks of homes and businesses in Greenwood, the prosperous black neighborhood of the booming oil city, burned to the ground after being looted by cheering whites; ten thousand black people left homeless.

No one was ever prosecuted.

Humiliation—and destruction—of a thriving black community, and of black life, due to white hostility. A century ago, and yet not.

Six months ago, Terence Crutcher, an unarmed black man, was shot to death in Tulsa by a white police officer, Betty Shelby. Video recordings showed he was leaning against his car with his hands up. Three days later, local activists marched downtown to demand justice, and criminal charges were quickly filed against Shelby. Yet a white Tulsan posted this threat in the comments section of a news report about the march:

Better remember last time blacks got rowdy in tulsa…they all died…we don’t play that round here…protest all you want…but get outta hand and we will put you back in check real quick. this isn’t St. Louis, block a road here you get ran over. Loot and riot you will join they fella you all are protesting for down at the local grave yard…keep it civil

“He immediately said, ‘Oh, I’m sorry, I shouldn’t have said that,’ but . . . it was . . . .” Mechelle Brown’s voice chokes, her lip quivers. “People who still think that would be an answer, that still think that would be okay. . . .”

We are sitting in Brown’s office at the Greenwood Cultural Center in Tulsa, where she serves as program director. We’ve come to Tulsa one week after Donald Trump’s election—two journalists from UU World, a twenty-something black man and a middle-aged white woman—to explore how racism and white supremacy operate in and beyond America’s legal system. We’re here as a team, certain that our different life experiences and identities will give us different lenses to make sense of what we find.

The Greenwood Cultural Center is an essential stop. Tulsans created it in 1995 to commemorate the riot, an event cloaked for decades in a conspiracy of silence born of shame and fear. Schools didn’t teach about the riot, and families—black and white—assiduously avoided the topic. Brown, like so many Tulsans, knew nothing about it until she was an adult. Threats to “put you back in check real quick” and other recent events have shaken her and convinced her that things haven’t changed much.

“It’s hard to not feel the same type of fear, that it doesn’t matter who you are, that you’ve never committed a crime.” Her voice breaks; she pauses, then gathers herself and continues: “That you’ve never shown any racism or violence toward anyone, it doesn’t matter, because when whites see me walking through the mall or my neighborhood, they only see me as black.”

She looks at us with a steady gaze. “There’s that part of me that wants to be so militant and pro-black and protect my family and community and be part of a movement that says, ‘We’ll be ready,’” she adds.

Both of us are surprised at her honesty, given that one of the journalists she’s speaking to is white.

Brown shakes her head slowly. “Then there’s the other part of me, that Jesus is love, is forgiveness and acceptance, and we have to operate in love, and we cannot buy into this fear,” she says. “No matter who is president, God is still God, and we can’t treat people based on what a few people will do.”

Riot and Remembrance: America’s Worst Race Riot and Its Legacy, by James S. Hirsch (Mariner Books, 2003)

The Burning: Massacre, Destruction, and the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, by Tim Madigan (St. Martin’s Griffin, 2003)

Tulsa Race Riot: A Report by the Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 (February 2001)

Through Brown’s window we see the train tracks that have served as this city’s black/white divide for more than a century. It was there that black men, many of them veterans of World War I, made an armed stand against the white mob that poured into Greenwood on the morning of June 1, 1921. Photographs of the riot are gruesome: charred bodies, men slain with guns by their side. On one photo, a panorama of the inferno, someone scrawled, “Runing [sic] the Negro out of Tulsa.”

Brown, who witnessed the Ku Klux Klan at her grandmother’s door in the 1970s, speaks softly: “When you look, after the Trump victory, and see so many people coming forward and so bold about their feelings about minorities, towards women, towards blacks—it’s a real wakeup call for just how far we have not come.”

How far we have not come. In 1921, 500 white civilians deputized by police became the “most dangerous part of the mob,” according to the National Guard. In 2015, a white retiree named Bob Bates shot and killed a black man, Eric Harris, while acting as a volunteer reserve deputy for the Tulsa County sheriff. On Good Friday 2012, two white men hunting for black people in North Tulsa shot three to death.

1921 is also the year that All Souls Unitarian Church in Tulsa, today the largest Unitarian Universalist congregation in the country, was cofounded by Richard Lloyd Jones, the conservative son of a prominent Unitarian minister. As owner and editor of the Tulsa Tribune newspaper, Jones played a significant role in fomenting the riot, most historians agree. Even as Jones worked to build a religiously liberal church in Tulsa, he was watering the seeds of white supremacy that encouraged the deadly riot and fostered a culture that reverberates today.

A daunting reality faces racial justice activists in Oklahoma. The state leads the nation in the incarceration of black men, with one in fifteen in prison. The proportion of black people on death row in the state is four times larger than in the general population.

Yet there are real signs of progress in this state where Trump won every county. In November, voters here also passed groundbreaking laws that cut penalties for nonviolent drug crimes. A review of the death penalty is underway. And Unitarian Universalists are playing crucial roles as racial justice advocates and bridge builders.

For all of Tulsa’s serious problems, this city of 400,000 is a place of deep connections. During our time here, we witness a lesson about human relationships and community. We, as strangers and journalists, are immediately welcomed by everyone we contacted and given generous amounts of their time. Even as we ask tough questions, the personal connection remains strong: people keep talking to us.

Still, the memory of the 1921 riot lingers like smoke from the thousands of torched black homes. The trauma of that horrific event has been passed from generation to generation, not necessarily consciously or openly but definitely, some told us. “My feeling is, a lot of the time people suffer from a feeling that there will be revenge motives like the massacre in 1921,” says the Rev. Gerald Davis, minister of the Church of the Restoration, a black UU church in Tulsa, and an affiliate minister at All Souls.

Brown also believes the riot helped create an ongoing culture of fear. However, she adds, “I feel hope for Tulsa because of people like Marq Lewis.”

Marq Lewis chants at a march in April 2015 calling for the firing of two Tulsa County sheriff’s deputies for their roles in the death of Eric Harris. (© Cory Young/Tulsa World via AP)

Marq Lewis moved to Tulsa from Atlanta nine years ago for a job. Laid off after four months, but motivated by his outrage over the stream of deaths of young black people at the hands of police nationwide, he decided to stay, and he founded an activist group called We the People Oklahoma that’s working within the system to make big change.

When Eric Harris was killed by a volunteer deputy who carried a gun at the sheriff’s authorization in 2015, Lewis leveraged an unusual Oklahoma law—with the help of a white lawyer, Laurie Phillips—that allows citizens to call for a grand jury. Lewis led a petition drive that got more than 8,000 signatures; criminal charges were filed against the sheriff, Stanley Glanz, and he resigned. Native-born Tulsans were stunned at Lewis’s success; many had told him it would never work.

TulsaPeople magazine named Lewis “Tulsan of the Year” in 2016, the first black person to receive that honor. He bounds in to meet us at Sisserou’s, a Caribbean restaurant frequented by a racially diverse population, where many people, including the restaurant owner, greet him enthusiastically.

Does Lewis believe in the justice system? “Yes, because I’ve seen it work,” he says. “If Oklahoma never had that [citizen petition] law, that man [Glanz] would still be in power now.”

Oklahoma has one of the highest rates of shootings of civilians by police. Yet three Oklahoma officers have been charged with crimes for killing civilians in the past ten years. In all three cases, the victim was black. In the first two cases, unlike most cases in other states, the officer was convicted; Betty Shelby is awaiting trial. “That’s unheard of anywhere in America,” Lewis says. What made it happen? “Pressure from the community!” he says. “Are there reforms needed? Yes, absolutely—citizen reforms.”

When Lewis arrived in Tulsa, the persistent shadow of the riot shocked him. “When I first moved here, I used to see black men walking around with heads down. That’s generations and generations of oppressed people feeling sectioned off, and feeling helplessness.”

But things are changing, and relatively quickly. “Today’s Tulsa is different from last year,” he says, with more activist organizations, a greater sense of citizen empowerment, and more ministers preaching about accountability and transparency.

Lewis sees Trump’s election as a wakeup call. “He made America realize we have a lot of work to do,” Lewis says, but “America has to figure out how to effect the change. Instead of crying, whining, complaining about it, be the change!”

In the days following Crutcher’s death, the Rev. Sheri Dickerson, executive director of Black Lives Matter Oklahoma (BLM OK), drove from Oklahoma City to Tulsa five times to meet with Lewis and Tulsa Police Chief Chuck Jordan.

A warm, energetic black woman who identifies as part of the LGBTQ community, Dickerson saw racially disparate reactions to the killing of Crutcher. “Black people walked around in numb shock for days after the tape’s release,” she said, adding that it connected to a “long legacy” of racial pain. But whites “wondered how could it happen in Oklahoma, because we pride ourselves on being a very polite people,” she says.

The Rev. Sheri Dickerson is executive director of Black Lives Matter Oklahoma. (© Brett Dickerson/Oklahoma City Free Press)

Dickerson, a Pentecostal minister, sits in the sanctuary of the Church of the Open Arms United Church of Christ in Oklahoma City, which provides office space to BLM OK. Dickerson is one of the church’s affiliate ministers.

She knew three of the thirteen black women that an Oklahoma City police officer, Daniel Holtzclaw, raped or sexually assaulted in 2013–2014. The case against Holtzclaw—who was convicted and is serving a 263-year sentence—fueled her commitment to building BLM OK as a force for justice. “We helped collect resources for the victims and let them know that they would never be alone in the courtroom,” she says. “These women need to know that they matter.”

Dickerson urges people to see the work of the movement for black lives as “legislative, to be sure,” but also “more than about policies and reforms.” And, she adds, BLM OK’s work—like so much in this state—“is about people. We started BLM here to have something before tragedy happens.”

“I walk with my faith helping keep me encouraged,” she says. “I can’t say this enough—the work has to be about real connections, real stories, and real people.”

Unitarian Universalist ministers, more than those from other religious traditions, are “not afraid to poke the bear,” Lewis tells us at Sisserou’s. He mentions with admiration the Rev. Marlin Lavanhar, senior minister at All Souls. Indeed, every person we interviewed in Tulsa spoke of Lavanhar and the racial justice work of All Souls.

Lavanhar tells us that the history of All Souls’s founding, by a racist, is never far from his mind. “In nature, wherever there’s a poison plant, the antidote is close by, within a couple of feet,” he says. “Even this person who helped create the context of this riot and death and destruction … created something that eventually became an antidote to that.”

Since 1960, when the Rev. Dr. John B. Wolf became its minister, All Souls has been on the frontlines of racial justice. In the ’60s and ’70s, Wolf led Tulsa’s progressive clergy in the fight for civil rights, and in the process, he lost congregants. “We had five millionaires when I arrived, this being an oil town, and I got rid of four of them that I know of!” says Wolf, now 91, with a raucous laugh.

Bishop Carlton Pearson and the Rev. Marlin Lavanhar greet worshipers at All Souls Unitarian Church in Tulsa. (© Doug Henderson)

On this November evening, Wolf, now minister emeritus, is sitting in the All Souls library with Lavanhar and two other All Souls ministers, the Rev. Gerald Davis and Bishop Carlton Pearson. Wolf tried to integrate the church in the ’60s but was able to attract no more than two dozen black members, mostly people new to Tulsa. In 2008, however, Pearson—a black prodigy of Oral Roberts—boosted All Souls’s black membership dramatically.

After Pearson was declared a heretic by his fellow Pentecostals for preaching universal salvation in the megachurch he led, he accepted Lavanhar’s invitation to lead worship at All Souls. He and approximately 200 of his parishioners started worshiping at All Souls in 2008, and today, about 4 percent of the church’s 2,023 members are black.

Read our prior coverage of All Souls in Tulsa:

“The Gospel of Inclusion,” by Kimberly French (Fall 2009)

“UUs Lead as Riot Survivors Receive Payments in Tulsa,” by Donald E. Skinner (May/June 2002)

Lavanhar was a leader in the call for reparations to survivors of the race riot, after a state commission made that recommendation in 2001. (The effort died after enormous political opposition.) After Trayvon Martin’s killing in 2012, Lavanhar wore a hoodie while preaching a sermon about “the new Jim Crow.” Lavanhar was the only white person invited to meet with a group of black ministers following the Good Friday shootings later that year.

But when Pearson and his parishioners—most of them black—started worshiping at All Souls and the church began offering a second service with a worship style rooted in black church traditions, a number of white members threatened to quit or withheld donations. To Lavanhar’s surprise, it wasn’t the church’s Republican members who complained about the changes; the members who left were Democrats. Lavanhar asked Wolf what he made of it.

During his ministry, Wolf found that Republicans typically stuck with him even when they strongly disagreed with his preaching on social or political issues. Republicans were there for religious freedom—and All Souls was the only church in town offering it—so they weren’t thrown off by things they didn’t necessarily support. But Democrats often have a much narrower tolerance for things they disagree with, Wolf said, such as the kind of cultural changes that Pearson and his parishioners brought—or even the idea that Republicans can be UUs, Lavanhar says. (He estimates that 15 percent of the church’s members are Republicans; 75 percent are Democrats.)

All Souls has created a Centennial Vision for 2021—the 100th anniversary of both the riot and the congregation’s founding—that promotes a multifaith and multiracial church. All Souls is running ads on black radio stations. It developed and offers programs on dismantling white supremacy. The programs have waiting lists including non-church members. The Rev. Barbara Prose, executive director of ministry at All Souls, says it is her goal for every congregant—and for Tulsa police and political leaders—to take the training. (Prose is happy to share the materials used in these programs with other UU congregations.)

“Especially considering our history around Richard Lloyd Jones, this is redemptive, really important for us,” says Lavanhar. “One of the core founders is implicated in the race riot, was clearly a racist, and we really think it’s a beautiful trajectory.”

As All Souls works to challenge its own founder’s toxic beliefs, its ministers hope their city can become a national leader in dismantling racism. “Tulsa has a great opportunity to do something great, and the people here to do it—with the young leadership, the ministers black and white, and All Souls’s model [as] a multicultural congregation that deals with hard questions,” says Davis. “All of that is happening right now in Tulsa, and that makes it unique.”

After eight years on the criminal court bench, Judge William C. Kellough lost his 2014 reelection campaign in a nonpartisan race in which his opponent nonetheless emphasized that Kellough was not only a Democrat but also a member of All Souls.

“Of course, that all blends into an accusation of [me] being soft on crime, which is interesting because I was endorsed by the D.A., the Fraternal Order of Police, and the police chief,” says Kellough, a third-generation Tulsan, with a sigh.

When he became a judge, Kellough says he immediately recognized the “obviously disproportionate number of defendants who were African American.” Most were charged with drug crimes, and he came to believe that only a small percentage were dangerous and should spend their lives in prison. But the Department of Corrections “focuses, even now, on prisons and jail cells and not programs,” he adds.

Kellough was the first judge to agree to try an experimental program, Women in Recovery, which diverts some women charged with nonviolent felonies from prison and instead helps them with housing, medical care, and job training. He sees the program as “one of the bright spots” in the criminal justice system, but it costs $1 million to $2 million a year, and so far, the entire cost has been covered by a private foundation.

Still, voters in November passed major reforms to state drug laws to keep more people from prison and funnel savings into treatment, and Kellough is feeling guardedly hopeful about the landscape. Now back in private practice, he’s excited about launching a diversion program for young men in conjunction with the public defender’s office.

Of the huge numbers of young black people in the system, he says, “We have to try to keep them out of prison and keep them from having felony convictions.”

Howard Barnett, too, is interested in reform. The president of Oklahoma State University in Tulsa, Barnett is a grandson of Richard Lloyd Jones, the cofounder of All Souls. Barnett and his cousin Georgia, who asked that her last name not be used, each tell us they believe their grandfather has been unjustly blamed for the riot, although they don’t disagree that his writings described black people in terrible terms.

Barnett, a white lawyer, sits on the Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission, which this spring will issue recommendations on the justice system. Only 27 percent of Oklahomans strongly support the death penalty, but regardless of one’s position, he says, there’s a problem with racial bias in the system.

“The chance of getting the death penalty, if a black man kills a white woman, is hugely higher than if a white man kills a white man,” he says. “It’s so statistically significant that it can’t not be a bias situation.” Given the proven unreliability of many types of forensic “evidence,” he favors reforms to reduce the likelihood of wrongful convictions. Tulsa voters just approved a tax increase to hire more community police officers, which Barnett says is a step in the right direction.

On any given day, the Tulsa County jail houses 1,500 people. With skylights and wide halls, it looks like a modernistic office building—until the iron doors slam behind you.

Recently, the Vera Institute of Justice found that the proportion of black people was four to five times higher in the Tulsa jail than in the general population. When Melissa Baldwin, co-chair of All Souls’s Criminal Justice Outreach program, tried to discuss those findings with a jail official, he scoffed. “He said, ‘That’s just a rumor,’” says Baldwin, who works as a criminal justice specialist with Mental Health Association Oklahoma, a nonprofit that promotes innovative reforms.

She shakes her head. “Bless his heart—he’s in that jail! You saw it. I saw it! I’ve seen the overrepresentation of people of color in our criminal justice system.” She sighs and adds, “It’s been in my heart.”

A white Tulsan who understands the city’s politically conservative culture, Baldwin says that widespread reforms won’t happen by directly naming the system’s racism. “Especially here in Oklahoma,” she adds, “you must be clear you’re talking about nonviolent offenders.” So she pitches pragmatism. “When I speak to the Chamber of Commerce, I talk about saving money,” she explains; for example, it costs around $1,300 a year to provide someone with outpatient mental health services versus $23,000 a year to incarcerate someone and give them those services.

In this close-knit city, racial justice reformers see building long-term relationships with law enforcement and others in power as vital work. About three years ago, in partnership with the city prosecutor and the municipal court judge, Mental Health Association Oklahoma launched a “special services” docket. It connects defendants charged with panhandling and other municipal crimes with housing, mental health, and substance abuse services. If they complete the program, charges are dismissed, which keeps defendants—most are very poor—out of jail while giving them help. Since employees of nonprofits run the program, it has cost the city nothing while saving taxpayers $900,000 and diverting 7,000 jail-days since 2014.

But are reforms enough? With such terrible racial disparity in the system, aren’t changes—even significant ones—simply perpetuating a grotesque racism that instead requires radical rethinking?

“If all we needed was a Band-Aid and some body cameras, we wouldn’t be where we are now,” says Ashley Boyd, a member of the Diverse Revolutionary Unitarian Universalist Multicultural Ministries (DRUUMM) steering committee.

Boyd is also part of the People’s Response Team, which documents the impact of police violence on the families of victims in Chicago. “When someone is shot or killed, whatever their story, it’s important for their families—and for police—to know the community cares and is watching,” Boyd says.

Boyd and others who believe the system is beyond reform say the modern U.S. criminal justice system was created to fill the economic holes created by the end of chattel slavery. It’s a theory supported by Michelle Alexander’s book The New Jim Crow and Ava DuVernay’s harrowing Netflix documentary 13th.

“I know social workers, lawyers, and others who are abolitionists because they’ve seen the system work up close. I don’t believe in this system,” she says, because “the system is doing what it’s designed to do”—oppress people of color.

At the Unitarian Universalist Association General Assembly in 2015, debate erupted over a proposed Action of Immediate Witness to support the Black Lives Matter movement. Nearly all delegates voiced strong support, but the resolution—drafted primarily by young UUs of color—affirmed “police reform and prison abolition.” That wording created a near crisis. An amendment ultimately ensured the passage of the resolution, but only by adding parenthetically, “(which seeks to replace the current prison system with a system that is more just and equitable).”

Abolishing prisons—or even policing—are radical solutions aimed at a deep and pervasive problem, Boyd and other advocates say. “We need a different sort of accountability system that does not rely on punishment,” she says. That means abolishing the system, a notion she understands frightens people but calls essential. “Oftentimes, UUs and others say, ‘I’m worried about your tactics, so I’m going to suggest this other thing that makes me more comfortable, but might not actually help you or other black people,’” Boyd says.

The Rev. Ashley Horan, executive director of the Minnesota UU Social Justice Alliance, is one of the foremost UU voices calling for dismantling the criminal justice system. “I don’t have to have been in prison or work in one to believe another way is possible,” says Horan, who is white. “I don’t buy anything that says we should listen to the agents of the system over the voices of those who have been harmed.” Horan asks UUs and others to focus less on the good work of individuals in the system and more on systems that are deeply unjust. “Abolition is both long-term, visionary work—it’s creating a world we have never seen before—and shorter-term work,” she says. “It means not building new prisons or increasing the militarization of police.”

Her vision, Horan says, “is not about police, it’s about policing. It’s not about good white people or bad white people but about white supremacy and whiteness. Yes, there are good police—but they are not good because they are police.”

“I think UUism as a whole can help here,” Boyd says. “There’s a spiritual problem of not seeing black folks as human beings, and our theology can respond to that.”

Horan believes UUs and other people of faith “dream big about what is possible—building and reconstructing and not just critiquing.” She isn’t certain the baggage-laden term “abolition” is the best one; nonetheless, she believes UUs have much to learn from liberation theology: “God loves all people, but God is going to side with the oppressed every time, and I wish our churches would, too.”

In Tulsa, a painful, racist history lives, as it lives throughout the United States: in deadly police-citizen “encounters,” in protests, in vicious online comments, and in elections.

History lives within the walls of All Souls. It lives in the green, empty spaces of Greenwood, where black businesses once thrived, and in the few black shops that survive ninety-five years after terror destroyed so many of their ancestors.

History lives, and it’s calling some Oklahomans to strive for change. Activists in Tulsa see their work as reforming the existing criminal justice system. Elsewhere, in different American places with different American histories, some voices are calling for more all-encompassing changes to dismantle what Boyd calls “unjust systems working as designed.”

What we found in Tulsa was not unbridled success in combating white supremacy. Indeed, an effort a decade ago to provide financial reparations to then-still-living survivors of the 1921 massacre failed in the face of powerful opposition. We instead found a community investing tremendous effort to continue the struggle.

In Tulsa’s Reconciliation Park, a third sculpture stands on the granite platform beside the figures of humiliation and hostility. Its name is not denial or forgetfulness. Its name is hope. Here in northeast Oklahoma, hope means community and persistence. Each time tragic injustice has arisen in Tulsa, so too has community in myriad forms. Sheri Dickerson drives 85 miles from Oklahoma City to Tulsa to join Marq Lewis because she’s needed. Laurie Phillips provides free legal counsel to We the People Oklahoma because she’s called. Marlin Lavanhar works for reparations and preaches while wearing a hoodie, in solidarity with Trayvon Martin, because he’s asked.

Black and white Tulsans are forcing the city, finally, to confront its racist past. Memories of the massacre in Greenwood now have public homes; the race riot is no longer forgotten. Elsewhere in the country, activists and faith leaders are attempting to do the same.

From our conversations with Oklahoman reformers and Midwestern abolitionists, we found an essential lesson: there is no one clear path to end white supremacy and other forms of systemic bigotry other than to rise up and face our shared, enduring, ugly past—and present—together.

Watch clergy respond in worship to this article and the work for racial justice at All Souls Unitarian Church in Tulsa, March 12, 2017.

Corrections

Earlier versions of this story, including in the print edition, misspelled Diverse Revolutionary Unitarian Universalist Multicultural Ministries.

This article appeared in the Spring 2017 issue of UU World under the title “Humiliation and Hostility: A Riot Lives On.”