Advertisement

When the Unitarian Universalist Church of Greater Lansing, Michigan, found itself without a building for the month of April due to construction, its senior minister, the Rev. Kathryn Bert, wasn’t sure what they would do. She reached out to members of her local minister’s association to see if another congregation could host them temporarily, but everyone used their space on Sunday.

Then she heard back from Imam Sohail Chaudhry, who leads the Islamic Center of East Lansing. The mosque’s gym was available on Sunday mornings. Would the church like to use it?

“Even the Jewish congregation used their sanctuary on Sunday morning, so they also would have us on Sunday afternoon,” Bert says. “The Islamic Center was the only place that we would be allowed to have services on Sunday morning. So that seemed like the best deal.”

The two congregations had a longstanding relationship. Chaudhry gave a sermon at the old church and did a presentation on Islam. Nic Cable, the church’s intern minister, also organized a resolution against Islamophobia with help from Chaudhry. (It passed the MidAmerica Region’s board in April; the General Assembly of the Unitarian Universalist Association adopted a version of that resolution in June.)

Those connections were key to the partnership’s success. But they don’t mean it was frictionless. Women had to decide whether to cover their heads out of respect when coming to UU services at the mosque, Bert says. (The mosque assured them either would be fine.) Some UUs, uncomfortable with mosque members showing them hospitality, jumped in to help clean up and put away chairs—a faux pas in many Muslim societies.

Both Bert and Chaudhry say those challenges helped the congregations grow closer. Chaudhry gave UUs tours of the mosque after their coffee hour, and many mosque members attended the Sunday services to learn about Unitarian Universalism. “It was a great mutual learning experience for both congregations,” Bert says.

What happened in Lansing is one example in a long history of Unitarian and Universalist interfaith work reaching back to the Transcendentalists, who helped popularize Eastern religious works in the United States. In one of the most famous passages from Walden, first published in 1854, Unitarian fellow traveler Henry David Thoreau reflected on seeing a group of workers cutting ice blocks from Walden Pond. “Thus it appears that the sweltering inhabitants of Charleston and New Orleans, of Madras and Bombay and Calcutta, drink at my well,” Thoreau wrote. “In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the Bhagvat-Geeta [sic] . . . in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial.”

Thirty years later, the Rev. James Freeman Clarke, a Unitarian minister, began teaching comparative religion at Harvard Divinity School. Clarke published the two-volume Ten Great Religions in 1871 and 1883, alongside Events and Epochs in Religious History in 1881. These works of comparative religion took non-Christian traditions seriously as sources of truth—albeit “ethnic,” “arrested,” and “partial,” from Clarke’s dated perspective.

The fiery Unitarian minister the Rev. Jenkin Lloyd Jones was general secretary of the group that organized the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893. He also sat on the organizing committee of the American Congress of Liberal Religion, which united Unitarians, Universalists, liberal Jews, and followers of Ethical Culture.

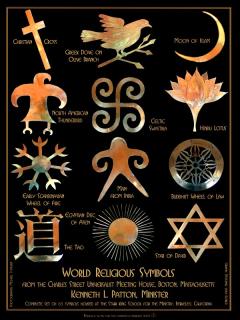

The Universalist Charles Street Meeting House in Boston placed these symbols of world religions around its sanctuary in the 1950s, inspiring other Unitarian and Universalist congregations to do the same. ( Available as a poster from the New York State Convention of Universalists.)

This thread of interest in non-Christian traditions runs through Universalist history, too. The Rev. Kenneth Leo Patton became minister of the experimental Charles Street Meeting House in Boston in 1949. There, Patton expanded the meaning of “universalist” from the Christian doctrine of universal salvation to one of universal religion—what he called “a religion for one world.”

Engagement with world religions, especially Asian traditions, is a unique part of Unitarian Universalist history, according to Emily Mace, director of the Harvard Square Library. But while many UUs take great pride in that inheritance, she says, it comes with complications. “There are still conversations going on, for good reasons, about cultural appropriation and so on,” Mace says. “But I do think that’s a unique feature of Unitarian Universalism.”

Another unique feature of Unitarian Universalist history is the denomination’s role in global interfaith work. In 1900, Unitarians helped found the world’s first international interfaith organization, the International Association for Religious Freedom (IARF). Coming on the heels of the Parliament of the World’s Religions, IARF promoted liberty of conscience in liberal religion around the world.

The group was especially important during the Cold War, when Unitarians in Eastern Europe found themselves under threat for their ethnic identities and religious views, according to the Rev. Eric Cherry, who directs the UUA’s International Office.

In the late 1960s, leaders of the UUA and Japan’s Rissho Kosei-kai lay Buddhist movement joined together to start an initiative that would grow into Religions for Peace, the world’s largest interfaith peace organization. The nongovernmental organization carries out its interfaith work at the highest levels of government and religious organizations, from the Vatican to the United Nations, as well as on the ground in areas of conflict around the world.

“It’s an interfaith dream come true, in the end,” Cherry says. “Unitarians and Buddhists and many others had a dream, and in this instance it absolutely came true.”

Both IARF and Religions for Peace are top-down groups whose work is largely carried out at the organizational level. Their brand of interfaith cooperation is head of communion to head of communion, not pew to pew. That’s starting to change, according to Cherry, as society becomes less hierarchical and politics become more democratic.

“In the twenty-first century, this work has been so much more about movements than about organizations,” he explains.

Today, two new initiatives are stretching the meaning of interfaith partnership. One is uniting faith communities to organize for social justice across lines of race and class. Another is bringing liberal religious leaders into conversation with unconventional spiritual communities to think through how they can all set a course through America’s changing religious landscape.

“I’m really excited about the enormous potential,” says UUA President Peter Morales. “The need out there is enormous. The real question is: Can denominations be agile enough to respond to it?”

One sign of that agility can be seen in a grassroots initiative that has caught fire at Unitarian Universalist congregations across the country. Congregation-based community organizations, or CBCOs, bring local congregations together across lines of neighborhood, religion, race, and class to advocate for social justice.

“I find that the multifaith community organizations are interested in building movement and power that leads to systemic change,” explains Susan Leslie, the UUA’s Congregational Advocacy and Witness Director.

Over 200 UU congregations across the country are active members of a CBCO, Leslie says. In Massachusetts, the Greater Boston Interfaith Organization has played a key role in developing affordable housing and pushing the statewide healthcare system that became a model for President Obama’s Affordable Care Act.

CBCOs bring clergy and laity together to hear each other’s stories and work together for change, according to Leslie. More engaged members might work in a small group with people of other races and classes, or from very different parts of their city. Leslie recalls ministers approaching her to complain that their CBCO wanted to focus on healthcare, for example, while their congregation was concerned about suburban sprawl. That can lead to important conversations, she says—especially when a relatively privileged congregation is confronting race and class for the first time.

“[I]f most of the people in your congregation didn’t have healthcare and were having to go to the emergency room all the time, you might be feeling that was more urgent than suburban sprawl,” she explains. “Right?”

Meanwhile, denominational leaders are finding new ways to connect across faiths. When Morales wanted help thinking through how to address the growing number of young people leaving organized religion, for example, he decided to call his colleagues in other liberal traditions to get their thoughts.

It’s a problem they all share. A 2012 survey by the Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion and Public Life found that 32 percent of adults under 30 were religiously unaffiliated, compared with just 15 percent of adults ages 50 to 64 and 9 percent of adults over 65. That’s a seismic shift that has sent panic through churches and synagogues as they watch their congregations shrink and their contributions dry up.

It’s not that young people are turned off to spirituality, according to Morales. Rather, he says, many don’t feel that organized religious institutions meet their needs or reflect their values. That’s borne out by the data. The 2012 Pew survey found that 68 percent of unaffiliated adults say they believe in God, while 37 percent identify as “spiritual and not religious,” and 21 percent pray daily.

“All these traditions are watching their young people drift away, in large number, in part because they don’t want to be confined,” Morales says. “It’s not that they’re rejecting the values they’ve been brought up with. But the fit institutionally isn’t very good.”

To find his way forward, Morales looked to the past. There’s a long history of liberal religious clergy working side by side, he says. Progressive ministers and rabbis marched side by side in the Civil Rights Movement and the fight for marriage equality, and they work shoulder to shoulder as chaplains in hospitals across the country.

That cooperation grows out of shared values, according to Morales. Unitarian Universalism and Reform Judaism, for example, come out of very different religious traditions. But they have similar views on questions like how to read scripture, the importance of science, and the nature of human gender and sexuality. In many ways, Morales says, the liberal branches of the various religious traditions share more in common with one another than they do with their more conservative coreligionists. “They get their cosmology from Scientific American, like I do,” he quips.

To get the conversation going, Morales reached out to the Rev. Geoffrey Black, then president of the United Church of Christ; Rabbi Rick Jacobs, president of the Union for Reform Judaism; and leaders of two interfaith groups, Religions for Peace and the United Religions Initiative. He wanted to know if they were interested in thinking together about how their traditions could find a way forward.

They jumped at the idea. Last year, the group of liberal religious leaders met for a day and a half of conversations at UUA headquarters in Boston. That led to a series of phone conversations among the busy group of religious leaders. In June, Rabbi Jacobs and the Rev. John Dorhauer—Goeffrey Black’s successor at the United Church of Christ—joined Morales at the UUA General Assembly, along with Naeem Baig, president of the Islamic Circle of America, where they pledged support for the movement for black lives (see page 26).

Now, they’re planning to widen the circle with help from two Harvard Divinity School students, Angie Thurston and Casper ter Kuile. Last April, Thurston and ter Kuile published How We Gather [PDF], a report that looked at new ways that many millennials are building community and meaning in their lives, from fitness communities like CrossFit and SoulCycle to explicitly spiritual groups like Juniper and The Sanctuaries.

Many millennials may not be in church or synagogue, Thurston and ter Kuile argue, but that doesn’t mean they’re not building their own communities of covenant. Now, the duo are helping Morales’ group of liberal religious leaders connect with some of these innovators. Together, they’re planning a larger meeting that brings the groups together.

What does an interfaith group of liberal religious leaders hope to learn from people running dinner parties for people who’ve experienced loss or exercise classes built around personal growth?

“We’re still in a very exploratory phase, and I think appropriately,” Morales says. “We don’t know what the answer is, but we’re convinced that we need to explore different ways of engaging people in our time—and that different faith traditions, we’re not in opposition to one another at all on this. We can learn from one another, and learn together.”

Back in Lansing, Michigan, the UU moved into its new building in June, with plans to host members of the mosque for a thank-you dinner. And the two congregations are already planning a joint service project with Habitat for Humanity.

Chaudhry says those kinds of connections are especially important now, given the hateful rhetoric against Muslims and refugees that has punctuated this election cycle. He points to times in the past when American Catholics and Jews faced similar prejudice. “I think it’s so important to reach out, promote education, get to know each other better,” Chaudhry says. “At the end of the day, we’re all human beings. We need to support each other in our difficult times.”